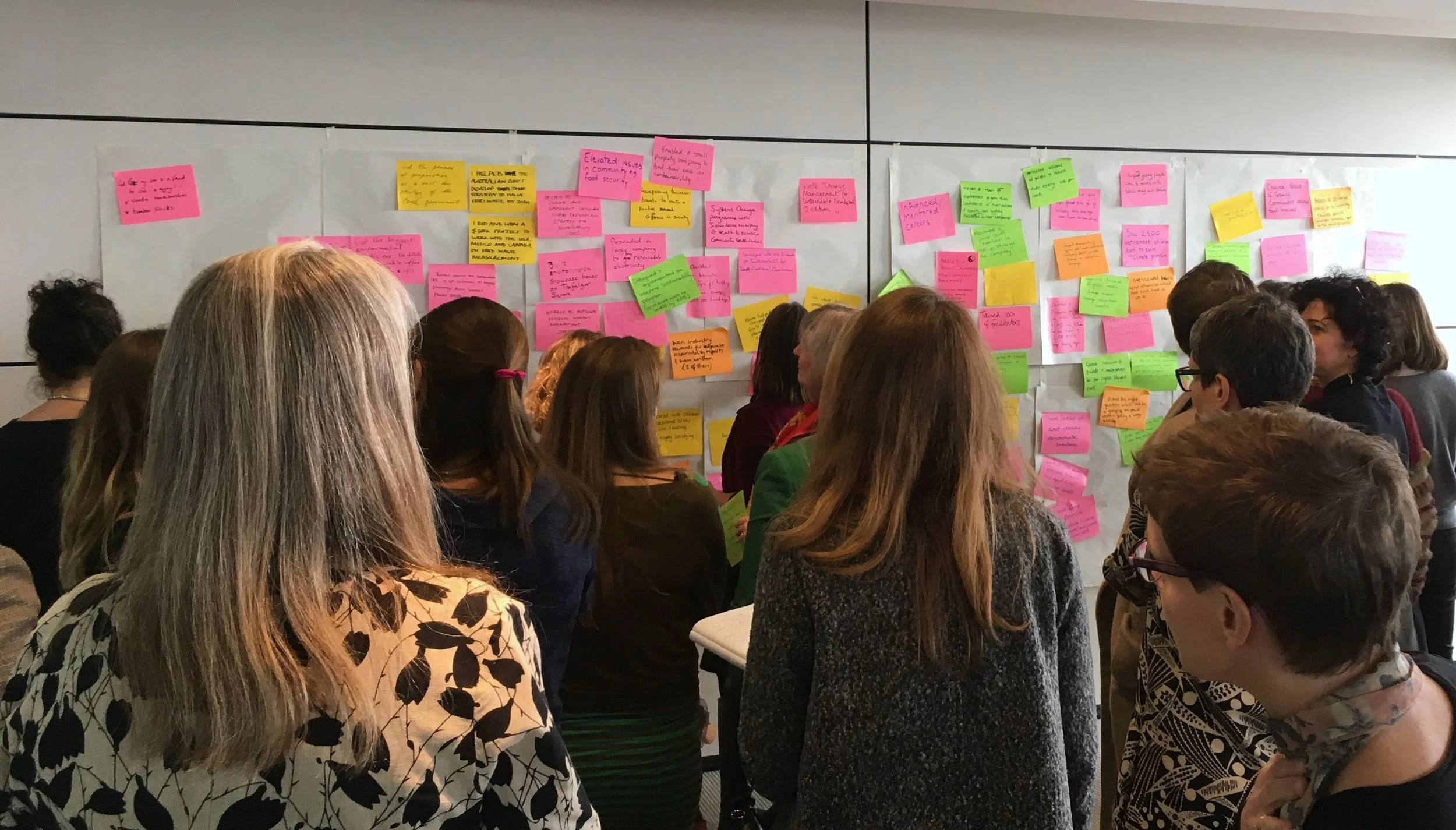

Lots of the women who came along to She is Still Sustainable said that the highlight was a co-coaching exercise we ran, using a solutions focus approach. People paired up and coached each other, asking positive, future-oriented questions about the sustainability work they wanted to do. The instructions are here.

Celebrate your achievements!

One of the lovely things that we did at She is Still Sustainable last month, was to build a wonderwall of our achievements. And wow! What a lot we have achieved.

Some were very personal – surviving divorce, arranging funerals, raising children....

Some had enormous reach – training 100s of facilitators, systems change programme with Sierra Leone Ministry of Health to improve community health, part of a team delivering a sustainable London 2012...

What difference do our differences make? Some thoughts on diversity in the sustainability profession

She is Still Sustainable was more workshop than a conference, but we did have two speaker panel sessions. Like other She is Sustainable events that came before ours, this included a presentation on some of the facts and figures showing the systemic disadvantages women experience in the workplace.

What has the snow revealed?

The Beast from the East has blanketed much of the UK with its beautiful sparkles, covering up roads, railways lines and in some cases front doors.

But the snow has also revealed things that aren’t usually seen: particulate pollution, uninsulated roofs, space which could be reclaimed from traffic for pedestrians and cyclists, and the impoverished nature of our soil.

Personal resilience - three ways to build yours

One of the things that came up again and again when I was talking to people about the new edition of Change Management for Sustainable Development, was supporting ourselves as sustainability professionals and as change-makers. There are three key pillars which support us: perspective, association, and giving ourselves a break.

Change management for sustainable development - 'a coach in your pocket'

Are you an environment or sustainability specialist, working to help your organisation step up to its role in bringing about a sustainable future? Want to make more of an impact? I want you to as well! Which is why I was so pleased when IEMA invited me to write a second edition of Change Management for Sustainable Development.

And when one of our peer readers said "it's like having a coach in your pocket", I was really happy, because that's exactly what I wanted it to be.

Surfing a wave of change - #OurBluePlanet

Final places remaining - book now! Still conversations for sustainability leaders

Where next for your sustainability strategy?

In these turbulent days, with right-wing populist movements rising and an unpredictable political context, you may be asking yourself how this should be reflected in your sustainability strategy.

Perhaps there are critical business and organisational issues which need addressing, regardless of political uncertainty.

Personal resilience hits a nerve

Every single place at this first still conversation has been snapped up - its theme of personal resilience has clearly touched a nerve. Coming along are people like the CEO of a sustainability NGO, the head of sustainability at a local authority, the group sustainability manager at a nationally known construction company and a director from a pioneering sustainable business think tank.

Still...... a new season of workshops for spring

Peer learning workshops - some emerging ideas

I'm excited about ideas for peer learning workshops that have been bubbling away in my head and are beginning to take shape.

Focused, coachy, peer learning

I want to bring together sustainability people of various kinds, to be able to talk with each other about their challenges and ideas in a more expansive and easeful way than a conference allows.

People really benefit from being able to think aloud in coaching conversations. I've seen the transformations that can happen when supportive challenge prompts a new way of looking at things.

We also get so much from comparing our own experiences with peers: finding the common threads in individual contexts, exploring ideas about ways forward.

I’d like to combine these things by making the peer learning available in smaller groups and smaller chunks, where the atmosphere is more like coaching.

What's the idea?

The idea is to run half-day workshops, with between 6 and 10 people at each event. The intention is that they are safe and supporting spaces, where people can talk freely. We'll meet in spaces that are relaxed, creative, private, energising and feel good to be in. (More comfortable than the stone steps in the picture.)

Each workshop would have a theme, to help focus the conversations and make sure people who come along have enough in common for those conversations to be highly productive.

I'd run a few, on different themes, and people can come to one, some or all of them. They don't have to come to them all, so the mix of people will be different for each workshop.

I'd charge fees, probably tiered pricing so that it's affordable for individuals and smaller not-for-profits, but commercial prices for bigger and for-profit organisations.

The content of each workshop will come from the participants, rather than me: my role is to facilitate the conversations, rather than to teach or train people.

Choices, dilemmas, testing

When I've tested this idea with a few people, many have said that the success of the workshops will depend on who else is there: people with experience, insight, credibility. People they feel able to trust, before they commit to booking. I think this is useful feedback.

On the other hand, I'm unsure about the best way to ensure this. Is it enough to include a description of "who these workshops are for" and leave it to people to decide for themselves? Or should I set up an application process of some kind: asking people who apply to include a short explanation of who they are, what their role and experience is, and why they want to come along.

If I set up an 'application' process, will that be off-putting to the naturally modest? Too cumbersome? Adding extra steps (apply, wait, get place confirmed, then pay...) feels risky: at each step, the pool of likely participants will get smaller. Will this make the workshops unviable? Who am I to choose, anyway?

Another option is to make the workshops 'by invitation' with people having the option of requesting an invitation for their friends, peers, colleagues - or even themselves. This is what I'm leaning towards at the moment, based on gut feel.

Will this increase people's confidence in the workshops - that not just anyone gets a place, their peers will provide quality reflections and be people worth meeting? Will it make those people who do get an invitation feel special, better about themselves?

And will I really turn down anyone who asks for an invitation? What will they feel?

I've set up a survey to gather views on this, as well as on the topics that will be most interesting to people. Please let me know here where's there a short survey. Discounts and prizes available!

How it feels to experiment

I'm not a natural entrepreneur. Some people love to experiment and learn from failure. Fail faster. Fail cheaper. Intellectually I'm committed to experimenting with these workshops: testing out ideas about formats, marketing, pricing, venues, topic focus vs emergence, length, the amount of 'taught' content vs 'created' content and so on.

Emotionally: not so much. I want to get everything right before I start (which is why it's taken me about six months to even get to this stage). I'm getting great support from lots of people, and boy do I need it. Even sitting here, I can feel the prickly, clammy, cold physical manifestations of the fear of failure.

I need to move through the fear and into the phase of actually running some test workshops. I know they'll be great. I can see the smiles, feel the warmth, visualise the kind of room we're meeting in and the I already have the design and process clear. I have a shelf of simple but beautiful props in my office. I am 100% confident about the events themselves, it's the communications and administration of the marketing that freaks me out.

Learning from the learning

So already I'm learning. About myself, about what people say they need, about how venues can be welcoming or off-putting, about how generous people are with their time and feedback.

She is Sustainable - sustaining the sustainers

Vertically, horizontally or circularly ambitious? Mothering or child-free, by choice or randomness? Urban or rural? Partnered for life or a free agent? Gay or straight or something else? Employed, entrepreneur or freelance?

Women who work in sustainability are all these things and more.

She is Sustainable was invented by five UK-based sustainability women (Becky Willis, Solitaire Townsend, Amy Mount, Hannah Hislop and Melissa Miners) who thought…

DareMini

So DareConfMini was a bit amazing. What a day. Highlights:

- Follow your jealousy from Elizabeth McGuane

- Situational leadership for ordinary managers from Meri Williams

- The challenge of applying the great advice you give to clients, to your own work and practice from Rob Hinchcliffe

- Finding something to like about the people who wind you up the most from Chris Atherton

- Being brave enough to reveal your weaknesses from Tim Chilvers

- Jungian archetypes to help you make and stick to commitments from Gabriel Smy

- Radical challenges to management orthodoxy from Lee Bryant

- Meeting such interesting people at the after party

No doubt things will continue to churn and emerge for me as it all settles down, and I'll blog accordingly.

In the meantime, all the videos and slides can be watched here and there are some great graphic summaries here (from Francis Rowland) and here (from Elisabeth Irgens)

There are also longer posts than mine from Charlie Peverett at Neo Be Brave! Lessons from Dare and Banish the January blues – be brave and get talking from Emma Allen.

If you are inspired to go to DareConf in September, early bird with substantial discounts are available until 17th February.

Many thanks to the amazing Jonathan Kahn and Rhiannon Walton who are amazing event organisers - and it's not even their day job. They looked after speakers very well and I got to realise a childhood fantasy of dancing at Sadler's Wells. David Caines drew the pictures.

I learn it from a book

Manuel, the hapless and put-upon waiter at Fawlty Towers, was diligent in learning English, despite the terrible line-management skills of Basil Fawlty. As well as practising in the real world, he is learning from a book. Crude racial stereotypes aside, this is a useful reminder that books can only take us so far. And the same is true of Working Collaboratively. To speak collaboration like a native takes real-world experience. You need the courage to practise out loud.

The map is not the territory

The other thing about learning from a book is that you'll get stories, tips, frameworks and tools, but when you begin to use them you won't necessarily get the expected results. Not in conversation with someone whose mother tongue you are struggling with, and not when you are exploring collaboration.

Because the phrase book is not the language and the map is not the territory.

Working collaboratively: a health warning

So if you do get hold of a copy of Working Collaboratively (and readers of this blog get 15% off with code PWP15) and begin to apply some of the advice: expect the unexpected.

There's an inherent difficulty in 'taught' or 'told' learning, which doesn't occur in quite the same way in more freeform 'learner led' approaches like action learning or coaching. When you put together a training course or write a book, you need to give it a narrative structure that's satisfying. You need to follow a thread, rather than jumping around the way reality does. Even now, none of the examples I feature in the book would feel they have completed their work or fully cracked how to collaborate.

That applies especially to the newest ones: Sustainable Shipping Initiative or the various collaborators experimenting with catchment level working in England.

Yours will be unique

So don't feel you've done it wrong if your pattern isn't the same, or the journey doesn't seem as smooth, with as clear a narrative arc as some of those described in the book.

And when you've accumulated a bit of hindsight, share it with others: what worked, for you? What got in the way? Which of the tools or frameworks helped you and which make no sense, now you look back at what you've achieved?

Do let me know...

Working collaboratively: world premiere!

So it's here! A mere nine months after first being contacted by Nick Bellorini of DōSustainability, my e-book on collaboration is out!

Over the next few weeks, I'll be blogging on some of the things that really struck me about writing it and that I'm still chewing over. In the meantime, I just wanted to let you know that it's out there, and you, dear reader, can get it with 15% off if you use the code PWP15 when you order it. See more here.

It's an e-book - and here's something cool for the dematerialisation and sharing economy geeks: you can rent it for 48 hours, just like a film! Since it's supposed to be a 90 minute read, that should work just fine.

Thanks!

And I couldn't have done it without the wonderful colleagues, clients, peers, critics, fellow explorers and tea-makers who helped out.

Andrew Acland, Cath Beaver, Craig Bennett, Fiona Bowles, Cath Brooks, Signe Bruun Jensen, Ken Caplan, Niamh Carey, Lindsey Colbourne, Stephanie Draper, Lindsay Evans, James Farrell, Chris Grieve, Michael Guthrie, Charlotte Millar, Paula Orr, Helena Poldervaart, Chris Pomfret, Jonathon Porritt, Keith Richards, Clare Twigger-Ross, Neil Verlander, Lynn Wetenhall; others at the Environment Agency; people who have been involved in the piloting of the Catchment Based Approach in England in particular in the Lower Lee, Tidal Thames and Brent; and others who joined in with an InterAct Networks peer learning day on collaboration.

Water wise: different priorities need different targeted engagement

For Diageo, the drinks company, agricultural suppliers typically represent more than 90% of its water footprint, so of course it's vital that the company’s water strategy looks beyond its own four walls to consider sustainable water management and risks in the supply chain. By contrast, what matters most for Unilever in tackling its global water footprint is reducing consumers’ water use when they are doing laundry, showering and washing their hair, particularly in countries where water is scarce.

Reflecting on a change that happened

Here's a nice exercise you can try, to help people base their thinking about organisational change on real evidence. Running workshop sessions on organisational change is a core part of my contribution to the various programmes run by the Cambridge Programme for Sustainability Leadership. This week, a group of people from one multi-national organisation met in Cambridge to further their own learning on sustainability and organisational responses to it. My brief was to introduce them to a little theory on organisational change, and help them apply it to their own situation.

Theory is all very well - I love a good model or framework. But sometimes people struggle to make the links to their experience, or they use descriptive models as if they were instructions.

This exercise gave them time to consider their direct experience of organisational change before the theory was introduced, so that they had rich evidence to draw on when engaging critically with the theory.

Step one - a change that happened

At tables, I asked them to identify a change that has happened in their organisation, of the same scale and significance as they think is needed in relation to sustainable development. All of the tables looked at some variation of the organisation's response to dramatically changing market conditions (engaging with a different customer base, redundancies).

Step Two - four sets of questions

I then asked the groups to discuss how this change really happened (not how the organisation's change policy manual said it should have happened). I offered four sets of questions:

- First inklings e.g. How did you know the change was coming? How did it begin? What happened before that? What happened after that? What changed first?

- People e.g. Who were the main characters who helped the change to happen? Who tried to stop it happening? Who was enthusiastic? Who was cynical? Who was worried?

- Momentum and confirmation e.g. What happened that provided confirmation that this change really is going to happen, that it’s not just talk? How was momentum maintained? What happened to win over the people who were unhappy?

- Completion and continuation e.g. Is the change complete, or are things still changing? How will (did) you know the change is complete?

Step Three - debrief

Discussions at tables went on for about 20 minutes, and then we debriefed in plenary.

I invited people to share surprises. Some of the surprises included the most senior person in the room realising that decisions made in leadership team meetings were seen as significant and directly influenced the way people did things - before the exercise, he had assumed that people didn't take much notice.

I also invited people to identify the things that confirmed that 'they really mean it', which seems to me to be a key tipping point in change for sustainability. Some of the evidence that people used to assess whether 'they really mean it' was interesting: the legal department drafting a new type of standard contract to reflect a new type of customer base; different kinds of people being invited to client engagement events. These 'artifacts' seemed significant and were ways in which the change became formalised and echoed in multiple places.

After the evidence, the theory

When I then introduced Schein's three levels of culture - still one of my favourite bits of organisational theory - the group could really see how this related to change.

Let me know how you get on, if you try this.

Leadership teams for collaboration

"Who will make sure it doesn't fall over?"

This was a question posed by someone in a workshop I facilitated, which brought together stakeholders (potential collaborators) who shared an interest in a water catchment.

It was a good question. In a collaboration, where equality between organisations is a value - and the pragmatic as well as philosophical truth is that everyone is only involved because they choose to be - what constitutes leadership? How do you avoid no-one taking responsibility because everyone is sharing responsibility?

If the collaboration stops moving forwards, like a bicycle it will be in danger of falling over. Who will step forward to right it again, give it a push and help it regain momentum?

Luxurious reading time

I've been doing some reading, in preparating for writing a slim volume on collaboration for the lovely people over at DōSustainability. (Update: published July 2013.) It's been rather lovely to browse the internet, following my nose from reference to reference. I found some great academic papers, including "Collaborative Governance in Theory and Practice" by Chris Ansell and Alison Gash. This paper is based on a review of 137 case studies, and draws out what the authors call 'critical variables' which influence the success of attempts at collaborative governance.

It's worth just pausing to notice that this paper focuses on 'collaborative governance', which you could characterise as when stakeholders come together to make decisions about what some other organisation is going to do (e.g. agree a management plan for a nature reserve ), to contrast it with other kinds of collaboration where the stakeholders who choose to collaborate are making decisions about what they themselves will do, to further the common or complementary aims of the collaboration (e.g. the emerging work of Tasting the Future).

Leadership as a critical variable

Ansell and Gash identify leadership as one of these critical variables. They say:

"Although 'unassisted' negotiations are sometimes possible, the literature overwhelmingly finds that facilitative leadership is important for bringing stakeholders together and getting them to engage each other in a collaborative spirit."

What kind of person can provide this facilitative leadership? Do they have to be disinterested, in the manner of an agenda-neutral facilitator? Or do they have to be a figure with credibility and power within the system, to provide a sense of agency to the collaboration?

Interestingly, Ansell and Gash think both are needed, depending on whether power is distributed relatively equally or relatively unequally among the potential collaborators. It's worth quoting at some length here:

"Where conflict is high and trust is low, but power distribution is relatively equal and stakeholders have an incentive to participate, then collaborative governance can successfully proceed by relying on the services of an honest broker that the respective stakeholders accept and trust."

This honest broker will pay attention to process and remain 'above the fray' - a facilitator or mediator.

"Where power distribution is more asymmetric or incentives to participate are weak or asymmetric, then collaborative governance is more likely to succeed if there is a strong "organic" leader who commands the respect and trust of the various stakeholders at the outset of the process."

An organic leader emerges from among the stakeholders, and my reading of the paper suggests that their strength may come from the power and credibility of their organisation as well as personal qualities like technical knowledge, charisma and so on.

While you can buy in a neutral facilitator (if you have the resource to do so), you cannot invent a trusted, powerful 'organic' leader if they are not already in the system. Ansell and Gash note "an implication of this contingency is that the possibility for effective collaboration may be seriously constrained by a lack of leadership."

Policy framework for collaboration

I'm also interested in this right now, because of my involvement in the piloting of the Catchment Based Approach. I have been supporting people both as a facilitator (honest broker) and by building the capacity of staff at the Environment Agency to work collaboratively and 'host' or 'lead' collaborative work in some of the pilot catchments. The former role has been mainly with Dialogue by Design, and latter with InterAct Networks.

One of the things that has been explored in these pilots, is what the differences are when the collaboration is hosted by the Environment Agency, and when it is hosted by another organisation, as in for example Your Tidal Thames or the Brent Catchment Partnership.

There was a well-attended conference on February 14th, where preliminary results were shared and Defra officials talked about what may happen next. The policy framework which Defra is due to set out in the Spring of 2013 will have important implications for where the facilitative leadership comes from.

One of the phrases used in Defra's presentation was 'independent host' and another was 'facilitator'. It's not yet clear what Defra might mean by these two phrases. I immediately wondered: independent of what, or of whom? Might this point towards the more agenda-neutral facilitator, the honest broker? If so, how will this be resourced?

I am thoughtful about whether these catchments might have the characteristics where the Ansell and Gash's honest broker will succeed, or whether they have characteristics which indicate an organic leader is needed. Perhaps both would be useful, working together in a leadership team.

Those designing the policy framework could do worse than read this paper.

What's it like from the inside?

You're trying to get your organisation to use sustainability thinking (social justice, ethics, environmental limits) to inform its strategy and practice. It can feel lonely. But you are not alone! There are thousands of sustainability change makers just like you in other organisations. What do your peers think and feel about this journey you are making apart, together? This survey gives a glimpse of how they see themselves, and the challenges they face. (Or, of how you see yourselves, since I expect some readers of this blog took part in the survey. Thanks!)

(Greener Management International has published the full article and you can read it here. There are other fascinating pieces in the same edition, including a couple on labeling / certification, and on organisational change strategies.)

Here are some of the headlines.

Just a job, or part of a wider movement?

The people who took part in the survey are working for change towards sustainability either as (part of) their job or through some recognised network of champions. But they do not see this as 'just a job'. Over 95% of them agreed with these two statements about why they do this work.

I want to do work which is in line with my values and interests.

It is my contribution to a wider change in society which I think needs to happen.

Are they changing their organisations?

So how are they doing: are their organisations changing? People used the Dunphy scale to show where their organisation was when they joined it and where they think it is now. They do indeed think that their organisations are changing, and mostly in the right direction! There has been a clear shift towards the right of Dunphy’s spectrum, and those respondents who have been in their organisation for longer have seen it move further, in line with what you'd hope and expect.

How much change is needed?

What's the perspective of these change agents, on how much change is needed? I asked:

To respond adequately to the challenge of sustainable development, how much change is needed?

These people think that radical, far-reaching change is needed in society as a whole, and substantial change is needed in their own organisations.

So the priority - where their skills and talents are most needed - is in the wider system. Are they happy that their own organisations seem to be on track? Not really.

Around 73% of organisational change agents for SD agreed or strongly agreed that they are dissatisfied with the pace and scale of change in their organisation. These people agreed strongly that the pace or scale (and sometimes both) were dissatisfying:

I feel and I see that changes are coming in many parts of my organisation but this process is far too slow.

My organisation has a culture which is generally slow to change—it is large, bureaucratic and hierarchical.

They shared some fascinating perspectives on what it feels like to be a change agent in these circumstances.

A lovely dilemma: we know that change needs to be democratic, and based on others understanding the ‘whys’, to avoid trying another oppressive regime. Experience seems to indicate that this requires patience, but patience in the faith that our mere acts now, however small, may lead to an exponential explosion in the ‘right’ activities, just in time . .. I now try to hold this tension very lightly and not let it distract me from what I’m doing day to day, in the moment. But I can’t pretend to be that successful at it . . .

With a perspective that this is a ‘human community’ not a machine! And that dissatisfaction needs to motivate (not frustration/anger etc.) and shape through positivity (not blind optimism or out-of-touchness) . . . And a personal sense of niche—what’s in my gift, power, influence etc. . . .

On being committed

We already know that our change agents see their work as 'more than just a job'.

How can climate change be just a job! I paraphrase Attenborough whose quote looms over my desk: ‘how could I look my child in the eye and say I knew what was happening to the world and did nothing’?

It is fantastic to feel passionate about my job. Having worked in this area, I now cannot see myself going back to a general management job even if that harms my promotion prospects.

It has to be a passion and something you believe in 100 per cent otherwise you can’t do the job properly, although I’ve had to learn to use the passion in presenting in a way that doesn’t scare the life out of people—in this country we still have a long, long journey.

You need to be really engaged in doing this and believe in it, if you are not the obstacles will be destructive for you personally and will demotivate you.

Does this 'life mission' attitude cause problems for them at work? Actually, only a minority said that it had (17% with their boss, 25% with colleagues). People said things like:

My boss is very ‘realistic’. He’s not big on challenging the current system etc. He has described his purpose as to be a ‘wet blanket’ on a lot of my ideas! At first I found this demotivating, but now I’ve tried to take the view that if I can persuade him of something, I can probably convince the rest of my organisation.

There is a danger that some may see some activities as a crusade, and so are not comfortable with this. Fortunately these people don’t fit the corporate vision and we can refer them back to the business case with the support of our top management. We recognise, reward and extol exemplar performance.

Am I making enough difference?

The responses are fairly evenly matched, with slightly more people satisfied with the difference they are making, but still a large minority disatisfied.

Reflections from some respondents showed a rather grudging or partial sense of satisfaction:

‘Enough of a difference’—well no, but no point in beating myself up and trading on guilt/fear—do that for too long (somewhat disagree).

I would like to make more of a difference, but feel that I’m doing what I can. More support from senior business managers would have much more of a positive impact than they realise. And not just financial support, actually understanding sustainable development and making positive contributions to it (somewhat disagree).

Changing the system

Some respondents expressed a sophisticated appreciation of the emergent and messy nature of system level change.

I think the struggle is needing to be seen to have an answer to a ‘wicked’ question. This need for ‘expertise’ and ‘answers’ may be better served by admitting we don’t know and then working together on potential solutions.

This understanding of change as emergent and systemic is not always easy to explain to colleagues and it may be hard to justify or have a sense of progress when working within this frame.

The change will be continuing, as sustainability is not an end state but a continual journey of improvement against ever increasing public perceptions of what is expected. This is a hard sell within an organisation!

I tend to work with people who have a common view that we are a catalyst for systemic change and our role is to convene and enable others to take innovative action towards that . . . this view is not shared by everyone in the organisation and this is where the tension comes in and the need to translate our work.

We are stuck in a world where mechanistic, linear approaches are foisted onto complex, systemic problems. This is where the tension lies for those involved in bridging this.

Some conclusions

- Our change agents believe that a very great deal of change is needed, to get on to the path to sustainability.

- They see change happening in their own organisations, but most of them do not think this change is rapid enough or seeks to go far enough.

- Our change agents do experience tensions. The biggest is the concern about the pace and scale of change in their organisation, and the second biggest is the difficulty of finding solutions which have both a business case and a values case.

- Some change agents find the paradigm of ‘solutions’ unhelpful: they see the change endeavour of which they are a part as systemic and emergent, rather than incremental and linear.

- This in itself can lead to tensions: how to tell if progressis being made, how to keep up colleagues’ morale and how to sell this approachto colleagues.

- Deciding the focus of change efforts and being a person who sees sustainability as ‘more than just a job’ are not a source of significant tension for most change agents, although many experience these tensions from time to time.

Fortunately, our change agents are not daunted by these tensions: they accept them as something which goes with the territory. Keep on keeping on, please!

This blog is based on "What's it like from the inside? The Challenges of Being an Organisational Change Agent for Sustainability" by Penny Walker, published in Greener Management International 57, May 2012.

Update

There's a fascinating account of the results of a much more in-depth piece of research by Christopher Wright, Daniel Nyberg and David Grant of the University of Sydney. They interviewed thirty six people who were "were either in designated positions in major Australian and global corporations as sustainability managers, or were working as external consultants advising about environmental sustainability", which is a similar set of professionals as in my survey. They distilled (or discerned) three distinct but related 'identities' : green change agent, rational manager and committed activist. They also found five narrative 'genres': achievement, transformation, epiphany, sacrifice and adversity. Well worth a close read, especially if you are a 'hippy on the third floor'.