"Shall we do this, then?" Silence is assent. It goes through 'on the nod'. And then you discover weeks later that no-one is actioning it and most people have no enthusiasm for it. How can you spot false consensus and help the group avoid settling for it?

Unlikely professions going green...

Earlier this summer saw the launch of London-based Lawyers for NetZero, a peer network for in-house counsel. But which other unlikely professions are changing from the inside out?

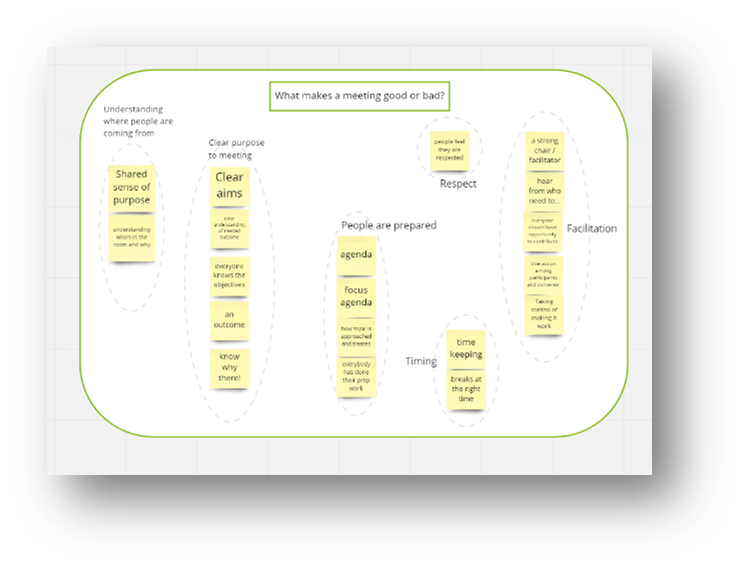

Meta plan or sticky note brainstorm - exploring a classic facilitation technique

When a facilitator invites a group to write multiple answers to an open question, put each one on a separate sticky-note and post them on a real or virtual wall, it's the first step in a classic technique called 'meta planning' (other names are available). So far, so good. But why do we do this and what happens next?

Task focus vs relationship focus: the 'trust cushion'

You've probably spotted that some people like to spend time getting to know others, building a strong relationship with them, and may let deadlines or quality slide so as to not fall out. They have a strong 'relationship focus'. Others like to know what's expected, what the deadlines are, and focus on delivery even if it means other people are side-lined or criticised. They have a strong 'task focus'. How can you persuade task-focussed people to put time into relationships?

Some ground rules for building trust

I’ve been working with a group of people from many different organisations who have been thrown into collaborating because of the pandemic.

They have achieved a lot, but when they took some time to reflect, they were able to see tensions which were exacerbated because they didn’t know each other very well and their ‘trust cushion’ was thin. So we experimented with some ground rules during a workshop session, all designed to help build trust.

Lessons from collaborating - #NeverMoreNeeded

A big picture take on strategic stakeholder engagement

Covid-19 and your meetings

Testing the water for collaboration

The most important sustainability challenges can only be solved by system change. And system change happens when people work together – collaborate - to change the system.

Collaboration is successful when the collaborators share some compelling aims. It’s not enough for everyone to nod along from the side-lines – they need to be rolling their sleeves up and getting stuck in to the game. How do you help potential collaborators find their shared aims?

Facilitating and convening when you're not neutral

Many organisations in the sustainability field do their best system-changing work when they are collaborating. And they find themselves in a challenging situation - playing the role of convening and facilitating, whilst also being a collaborator, with expertise and an opinion on what a good outcome would look like and how to get to it. This dual role causes problems. Here’s how to fix them.

Peer learning workshops - some emerging ideas

I'm excited about ideas for peer learning workshops that have been bubbling away in my head and are beginning to take shape.

Focused, coachy, peer learning

I want to bring together sustainability people of various kinds, to be able to talk with each other about their challenges and ideas in a more expansive and easeful way than a conference allows.

People really benefit from being able to think aloud in coaching conversations. I've seen the transformations that can happen when supportive challenge prompts a new way of looking at things.

We also get so much from comparing our own experiences with peers: finding the common threads in individual contexts, exploring ideas about ways forward.

I’d like to combine these things by making the peer learning available in smaller groups and smaller chunks, where the atmosphere is more like coaching.

What's the idea?

The idea is to run half-day workshops, with between 6 and 10 people at each event. The intention is that they are safe and supporting spaces, where people can talk freely. We'll meet in spaces that are relaxed, creative, private, energising and feel good to be in. (More comfortable than the stone steps in the picture.)

Each workshop would have a theme, to help focus the conversations and make sure people who come along have enough in common for those conversations to be highly productive.

I'd run a few, on different themes, and people can come to one, some or all of them. They don't have to come to them all, so the mix of people will be different for each workshop.

I'd charge fees, probably tiered pricing so that it's affordable for individuals and smaller not-for-profits, but commercial prices for bigger and for-profit organisations.

The content of each workshop will come from the participants, rather than me: my role is to facilitate the conversations, rather than to teach or train people.

Choices, dilemmas, testing

When I've tested this idea with a few people, many have said that the success of the workshops will depend on who else is there: people with experience, insight, credibility. People they feel able to trust, before they commit to booking. I think this is useful feedback.

On the other hand, I'm unsure about the best way to ensure this. Is it enough to include a description of "who these workshops are for" and leave it to people to decide for themselves? Or should I set up an application process of some kind: asking people who apply to include a short explanation of who they are, what their role and experience is, and why they want to come along.

If I set up an 'application' process, will that be off-putting to the naturally modest? Too cumbersome? Adding extra steps (apply, wait, get place confirmed, then pay...) feels risky: at each step, the pool of likely participants will get smaller. Will this make the workshops unviable? Who am I to choose, anyway?

Another option is to make the workshops 'by invitation' with people having the option of requesting an invitation for their friends, peers, colleagues - or even themselves. This is what I'm leaning towards at the moment, based on gut feel.

Will this increase people's confidence in the workshops - that not just anyone gets a place, their peers will provide quality reflections and be people worth meeting? Will it make those people who do get an invitation feel special, better about themselves?

And will I really turn down anyone who asks for an invitation? What will they feel?

I've set up a survey to gather views on this, as well as on the topics that will be most interesting to people. Please let me know here where's there a short survey. Discounts and prizes available!

How it feels to experiment

I'm not a natural entrepreneur. Some people love to experiment and learn from failure. Fail faster. Fail cheaper. Intellectually I'm committed to experimenting with these workshops: testing out ideas about formats, marketing, pricing, venues, topic focus vs emergence, length, the amount of 'taught' content vs 'created' content and so on.

Emotionally: not so much. I want to get everything right before I start (which is why it's taken me about six months to even get to this stage). I'm getting great support from lots of people, and boy do I need it. Even sitting here, I can feel the prickly, clammy, cold physical manifestations of the fear of failure.

I need to move through the fear and into the phase of actually running some test workshops. I know they'll be great. I can see the smiles, feel the warmth, visualise the kind of room we're meeting in and the I already have the design and process clear. I have a shelf of simple but beautiful props in my office. I am 100% confident about the events themselves, it's the communications and administration of the marketing that freaks me out.

Learning from the learning

So already I'm learning. About myself, about what people say they need, about how venues can be welcoming or off-putting, about how generous people are with their time and feedback.

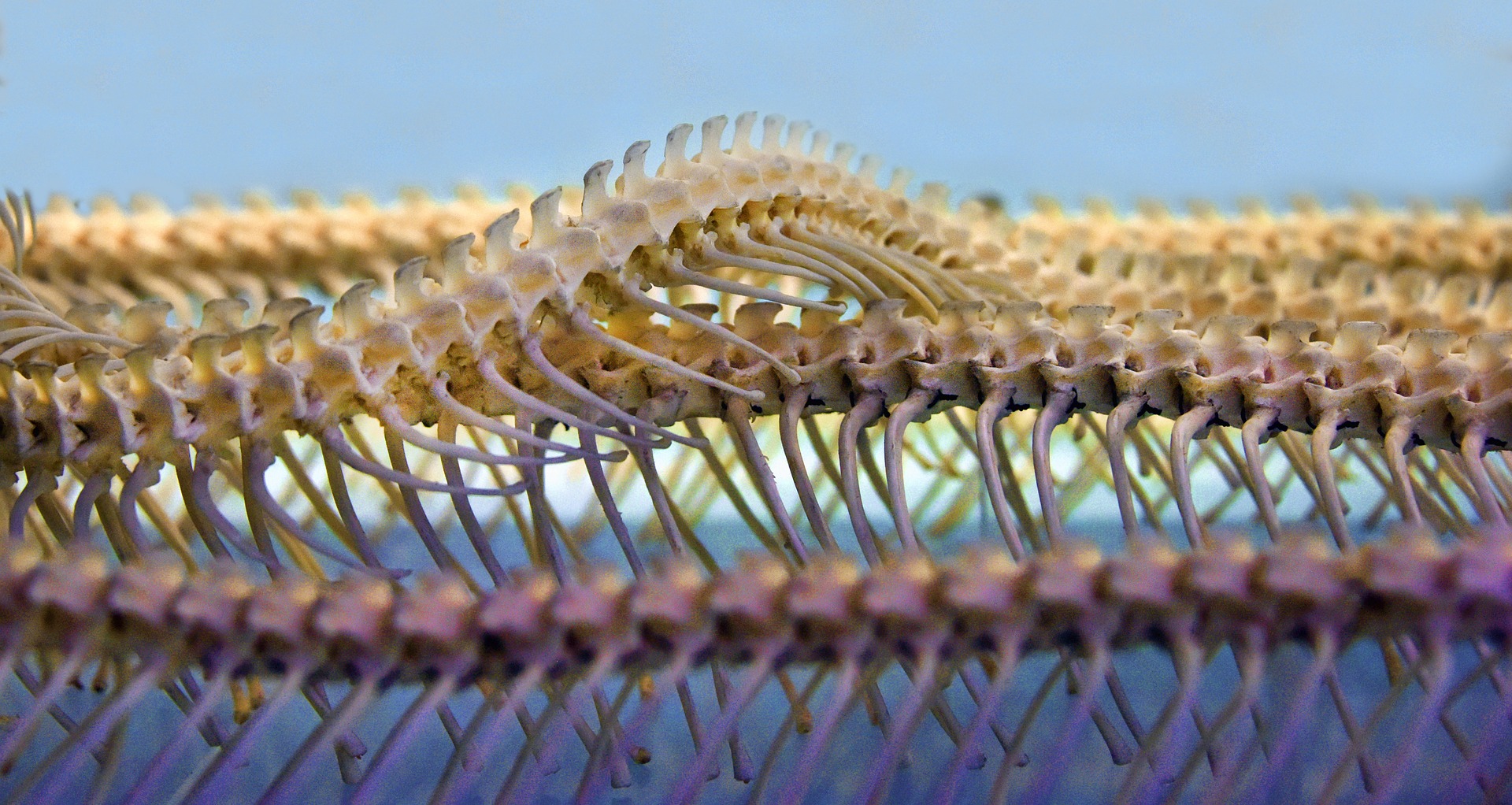

Give your collaboration some backbone!

All collaborations need a strong, flexible backbone, holding it all together, channelling communication and letting the interesting bits get on with what they’re really good at. I first came across the term ‘backbone organisation’ in the work of US organisation FSG, writing about what they call collective impact, but the need for a central team of some sort has been obvious throughout my work on collaboration. What is the ‘backbone’, and what does it do?

Has there been a tipping point for sustainable business?

Sustainability types were discussing the Sustainable Development Goals (aka Global Goals) in London last night, at a regular meeting of The Crowd. If you are twitter-enabled, you can search for the #crowdforum tweets to follow that way.

I've got very interested in the SDGs, since being asked to write a series of articles about how business is responding, for The Environmentalist.

There was some great conversation, and I was particularly struck by Claire Melamed's view that businesses can cherry pick (or have strategic priorities) among the SDGs, as long as a business doesn't actively undermine any of the goals or targets. That seems a pretty clear minimum ask!

How would you tell if a goal is being actively undermined?

So how would you tell? Perhaps the easiest is to do an audit-style check against all 169 of the targets, and spot the krill oil which is staining the otherwise spotless business practices. Some will be easier to test than others, so the views of stakeholders will probably be useful in helping see the business's practices from a variety of angles.

What are the sanctions and disincentives?

The people who spoke about this seemed to be relying on good old fashioned campaigns to bring the undermining to public attention and turn it into a business issue for the company concerned. Which seems pretty familiar to me. One person used the Greenpeace campaign against the use of unsustainable palm oil by Nestle's Kit Kat as an example. And that campaign was way back in 2010. Friends of the Earth was launched in the UK with a mass bottle dump outside Schweppes headquarters, which became a well-known photo at the time. Social media ensures that campaigns like this can become viral in a few hours. But in essence they are nothing new.

Another person said "you'd have to be not in your right mind, to actively undermine any of these goals." And perhaps she's right. But it's clear that either lots of people haven't been in their right minds, or perhaps it's been perfectly rational to undermine social and ecological life support systems, because we are here and here isn't a great place for many of the critical issues highlighted by the global goals. Once again I find myself wobbling between irrational optimism and chronic unease.

But let's give this optimist the benefit of the doubt, and assume that it is now rational to avoid actively undermining the goals.

What's changed?

The claim was made, with some strength of feeling, that COP21's agreement in Paris has made a tangible difference, with analysts using climate and fossil fuel exposure to make investment recommendations. And there seemed to be general agreement in the room that this was new and significant. And today, two days after the Crowd forum event, comes the news that Peabody Energy (the world's biggest privately-owned coal producer) has filed for bankruptcy. So that's one of the 17 goals accounted for.

Other voices suggested that the 17 goals will set a broad context for action by policy makers and government, helping business decision-makers have more certainty about what the future holds and therefore being more confident to invest in goal-friendly products, services and ways of doing business. On the other hand, people noticed the apparent disconnect between the UK Government's pledges in Paris, and its action to undermine renewables and energy efficiency, and support fossil fuel extraction, in the subsequent budget and policy decisions.

Another change was the rise of the millenials, who make up increasing proportions of the workforce, electorate and buying public. Their commitment to values was seen as a reason for optimism, although there was also a recognition that we can't wait for them to clear up our mess. (As someone who still clears up her own millenial children's mess, while said young people are jetting off and buying fast fashion off the interwebs, I am perhaps a little cynical about how values translate into action for this generation.)

And the final bid for what's changed, is the recognition and willingness of players to collaborate in order to create system-level change. And the good news on this is that there is a lot of practical understanding being shared about how to make collaboration work (Working Collaboratively is just one contribution to this), and specialist organisations to help.

So has there been a tipping point?

Lots of people were insisting to me that there has. There were few negative voices. In fact, some contributors said they were bored and in danger of falling asleep, such was the level of agreement in the room. I was left with the impression that we're getting close to a critical mass of business leaders wanting to do the right thing, and they need support and pressure from the rest of us to make it in their short-term interests to do so.

So is it back to the placards, or sticking with the post-it notes?

Who are "we"?

When people are collaborating or working in groups, there is sometimes ambiguity about where things (like policy decisions, research briefings, proposals) have come from, and who is speaking for whom. If you are convening a collaboration (or being a “backbone” organisation) this can be especially sensitive. Collaborating organisations may think that when you say “we”, you mean “we, the convenor team” when in fact you mean “we, all the collaborating organisations in this collaboration”. Or vice versa. This can lead to misunderstanding, tension, anger if people think you are either steam-rollering them or not properly including them.

Who are 'You'?

In general, think about whether to say “you” or “we”. When you use "you", there's a very clear divide between yourself and the people you are addressing. This is often going to be unhelpful in collaboration, as it can reinforce suspiscions that the collaboration is not a coalition of willing equals, but somehow a supplicant or hierarchical relationship.

Who are 'we'?

“We” is clearly more collaborative, BUT the English language is ambiguous here, so watch out!

“We” can mean

‘me and these other people, not including you’

(This is technically called ‘exclusive we’, by linguists.)

Or

‘me and you’ (and maybe some other people).

(‘Inclusive we’, to linguists.)

If you mean ‘me and you’, but the reader or listener hears ‘me and these other people, not including you’, then there can be misunderstandings.

For this reason, it can be helpful to spell out more clearly who you mean rather than just saying ‘we’.

What might this look like in practice?

These are examples from real work, anonymised.

In a draft detailed facilitation plan for a workshop, the focus question proposed was:

"What can we do to enable collaborative working?”

It was changed to:

“What can managers in our respective organisations do to enable collaborative working?”

The ‘we’ in original question was meant to signify “all of us participating in this session today” but the project group commenting on the plan interpreted it as “the organisers”. The new wording took out ‘we’ and used a more specific set of words instead.

A draft workshop report contained this paragraph:

“We do not have an already established pot of money for capital programmes that may flow from this project. One opportunity is to align existing spend more effectively to achieve the outcomes we want.”

This was changed to:

“[XXX organisation] does not have an already established pot of money for capital programmes that may flow from this project. One opportunity is to align existing spend more effectively to achieve the outcomes agreed by [YYY collaboration].”

Both uses of ‘we’ were ambiguous. The first meant ‘The convening organisation’. The second meant ‘we, the organisations and people involved in agreeing outcomes’.

The changes make this crystal clear.

Cometh the "our"

The same ambiguity applies with ‘our’. For example, when you refer to “our plan” be clear whether you mean “[Organisation XXX]’s plan” or “the plan owned by the organisations collaborating together”.

Acknowledgements

This post was originally written by Penny Walker, in a slightly different form, for a Learning Bulletin produced by InterAct Networks for the Environment Agency as part of its catchment pilot programme.

For more exciting detail on 'clusivity', including a two-by-two matrix, look here.

InterAct Networks - thank you for a wonderful ride

For over fifteen years, InterAct Networks worked to put stakeholder and public engagement at the heart of public sector decision-making, especially through focusing on capacity-building in the UK public sector. This work - through training and other ways of helping people learn, and through helping clients thinks about structures, policies and organisational change - helped organisations get better at strategically engaging with their stakeholders to understand their needs and preferences, get better informed, collaboratively design solutions and put them into practice. Much of that work has been with the Environment Agency, running the largest capacity-building programme of its kind.

History

InterAct Networks was registered as a Limited Liability Partnership in February 2002.

Founding partners Jeff Bishop, Lindsey Colbourne, Richard Harris and Lynn Wetenhall established InterAct Networks to support the development of 'local facilitator networks' of people wanting to develop facilitation skills from a range of organisations in a locality.

These geographically based networks enabled cross organisational learning and support. Networks were established across the UK, ranging from the Highlands and Islands to Surrey, Gwynedd to Gloucestershire. InterAct Networks provided the initial facilitation training to the networks, and supported them in establishing ongoing learning platforms. We also helped to network the networks, sharing resources and insights across the UK. Although some networks (e.g. Gwynedd) continue today, others found the lack of a 'lead' organisation meant that the network eventually lost direction.

In 2006, following a review of the effectiveness of the geographical networks, InterAct Networks began working with clients to build their organisational capacity to engage with stakeholders (including communities and the public) in decision making. This work included designing and delivering training (and other learning interventions), as well as setting up and supporting internal networks of engagement mentors and facilitators. We have since worked with the Countryside Council for Wales, the UK Sustainable Development Commission, Defra, DECC (via Sciencewise-ERC see p10), Natural England and primarily the Environment Agency in England and Wales.

Through our work with these organisations InterAct Networks led the field in:

diagnostics

guidance

tools and materials

new forms of organisational learning.

After Richard and Jeff left, Penny Walker joined Lindsey and Lynn as a partner in 2011, and InterAct Networks became limited company in 2012. In 2014, Lynn Wetenhall retired as a Director.

Some insights into building organisational capacity

Through our work with clients, especially the Environment Agency, we have learnt a lot about what works if you want to build an organisation's capacity to engage stakeholders and to collaborate. There is, of course, much more than can be summarised here. Here are just five key insights:

- Tailor the intervention to the part of the organisation you are working with.

- For strategic, conceptual 'content', classroom training can rarely do more than raise awareness.

- Use trainers who are practitioners.

- Begin with the change you want to see.

- Learning interventions are only a small part of building capacity.

Tailor the intervention

An organisation which wants to improve its engagement with stakeholders and the public in the development and delivery of public policy needs capacity at organisational, team and individual levels.

This diagram, originated by Jeff Bishop, shows a cross-organisational framework, helping you to understand the levels and their roles (vision and direction; process management; delivery). If capacity building remains in the process management and delivery zones, stakeholder and public engagement will be limited to pockets of good practice.

Classroom training will raise awareness of tools

There are half a dozen brilliant tools, frameworks and concepts which are enormously helpful in planning and delivering stakeholder and public engagement. Classroom training (and online self-guided learning) can do the job of raising awareness of these. But translating knowledge into lived practice - which is the goal - needs ongoing on-the-job interventions like mentoring, team learning or action learning sets. Modelling by someone who knows how to use the tools, support in using them - however inexpertly at first - and reinforcement of their usefulness. Reflection on how they were used and the impact they had.

Use trainers who are practitioners

People who are experienced and skillful in planning and delivering stakeholder and public engagement, and who are also experienced and skillful in designing and delivering learning interventions, make absolutely the best capacity-builders. They have credibility and a wealth of examples, they understand why the frameworks or skills which are being taught are so powerful. They understand from practice how they can be flexed and when it's a bad idea to move away from the ideal. We were enormously privileged to have a great team of practitioner-trainers to work with as part of the wider InterAct Networks family.

Begin with the change you want to see

The way to identify the "learning intervention" needed, is to begin by asking "what does the organisation need to do differently, or more of, to achieve its goals?", focusing on whatever the key challenge is that the capacity building needs to address. Once that is clear (and it may take a 'commissioning group' or quite a lot of participative research to answer that question), ask "what do (which) people need to do differently, or more of?". Having identified a target group of people, and the improvements they need to make, ask "what do these people need to learn (knowledge, skills) in order to make those improvements?". At this stage, it's also useful to ask what else they need to help them make the improvements (permission, budget, resources, changes to policies etc). Finally, ask "what are the most effective learning interventions to build that knowledge and those skills for these people?". Classroom training is only one solution, and often not the best one.

Learning interventions are (only) part of the story

Sometimes the capacity that needs building is skills and knowledge - things you can learn. So learning interventions (training, coaching, mentoring etc) are appropriate responses. Sometimes the capacity "gap" is about incentives, policies, processes or less tangible cultural things. In which case other interventions will be needed. The change journey needs exquisite awareness of what 'good' looks like, what people are doing and the impact it's having, what the progress and stuckness is. Being able to share observations and insights as a team (made up of both clients and consultants) is invaluable.

The most useful concepts and frameworks

Over the years, some concepts and frameworks emerged as the most useful in helping people to see stakeholder engagement, collaboration and participation in a new light and turn that enlightenment into a practical approach.

I've blogged about some of these elsewhere on this site: follow the links.

- What's up for grabs? What's fixed, open or negotiable.

- Asking questions in order to uncover latent consensus - the PIN concept.

- How much engagement? Depending on the context for your decision, project or programme, different intensities of engagement are appropriate. This tool helps you decide.

- Is collaboration appropriate for this desired outcome? This matrix takes the 'outcome' that you want to achieve as a starting point, and helps you see whether collaborating with others will help you achieve it.

- Engagement aims: transmit, receive and collaborate. Sometimes known as the Public Engagement Triangle, this way of understanding "engagement aims" was developed originally by Lindsey Colbourne as part of her work with the Sciencewise-ERC, for the Science for All Follow Up Group.

- Who shall we engage and how intensely? (stakeholder identification and mapping)

Three-day facilitation training

As part of this wider suite of strategic and skills-based capacity building, InterAct Networks ran dozens of three-day facilitation skills training courses and helped the Environment Agency to set up an internal facilitator network so that quasi-third parties can facilitate meetings as part of public and stakeholder engagement. The facilitator network often works with external independent facilitators, contracted by the Environment Agency for bigger, more complex or higher-conflict work. This facilitation course is now under the stewardship of 3KQ.

More reports and resources

Here are some other reports and resources developed by the InterAct Networks team, sometimes while wearing other hats.

Evaluation of the use of Working with Others - Building Trust for the Shaldon Flood Risk Project, Straw E. and Colbourne, L., March 2009.

Departmental Dialogue Index - developed by Lindsey Colbourne for Sciencewise.

Doing an organisational stocktake.

Organisational Learning and Change for Public Engagement, Colbourne, L., 2010, for NCCPE and The Science for All group, as part of The Department of Business, Innovation and Skills (BIS)’ Science and Society programme.

Mainstreaming collaboration with communities and stakeholders for FCERM, Colbourne, L., 2009 for Defra and the Environment Agency.

Thank you for a wonderful ride

In 2015, Lindsey and Penny decided to close the company, in order to pursue other interests. Lindsey's amazing art work can be seen here. Penny continues to help clients get better at stakeholder engagement, including through being an Associate of 3KQ, which has taken ownership of the core facilitation training course that InterAct Networks developed and has honed over the years. The Environment Agency continues to espouse its "Working with Others" approach, with great guidance and passion from Dr. Cath Brooks and others. Colleagues and collaborators in the work with the Environment Agency included Involve and Collingwood Environmental Planning, as well as Helena Poldervaart who led on a range of Effective Conversations courses. We hope that we have left a legacy of hundreds of people who understand and are committed to asking great questions and listening really well to the communities and interests they serve, for the good of us all.

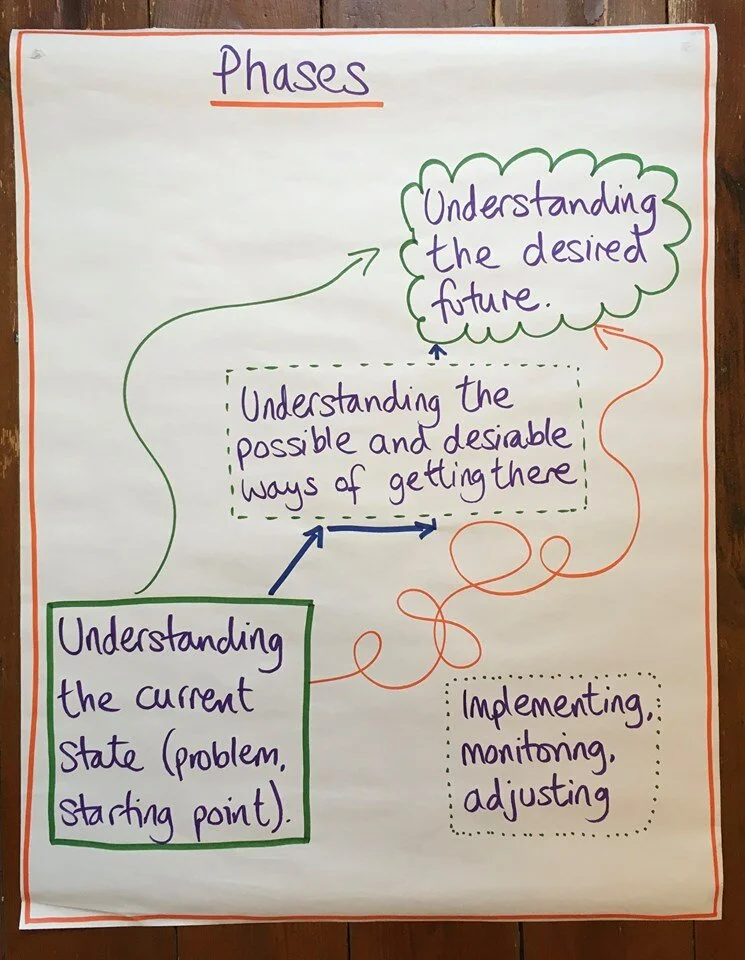

There are phases, in collaboration

One of the useful analytical tools which we've been using in training recently, is the idea of there being phases in collaborative working. This diagram looks particularly at the long, slow, messy early stages where progress can be faltering.

Learning sets, debriefing groups: learning from doing

I've been helping organisations learn how to collaborate better. One of my clients was interested in boosting their organisation's ability to keep learning from the real-life experiences of the people who I'd trained.

We talked about setting up groups where people could talk about their experiences - good and bad - and reflect together to draw out the learning. This got me thinking about practical and pragmatic ways to describe and run learning sets.

Action learning sets

An action learning set is – in its purest form – a group of people who come together regularly (say once a month) for a chunk of time (perhaps a full day, depending on group size) to learn from each other’s experiences. Characteristics of an action learning set include:

- People have some kind of work-related challenge in common (e.g. they are all health care workers, or all environmental managers, or they all help catalyse collaboration) but are not necessarily all working for the same organisation or doing the same job.

- The conversations in the 'set' meetings are structured in a disciplined way: each person gets a share of time (e.g. an hour) to explain a particular challenge or experience, and when they have done so the others ask them questions about it which are intended to illuminate the situation. If the person wants, they can also ask for advice or information which might help them, but advice and information shouldn’t be given unless requested. Then the next person gets to share their challenge (which may be completely different) and this continues until everyone has had a turn or until the time has been used up (the group can decide for itself how it wants to allocate time).

- Sometimes, the set will then discuss the common themes or patterns in the challenges, identifying things that they want to pay particular attention to or experiment with in their work. These can then be talked about as part of the sharing and questioning in the next meeting of the set.

- So the learning comes not from an expert bringing new information or insight, but from the members of the set sharing their experiences and reflecting together. The ‘action’ bit comes from the commitment to actively experiment with different ways of doing their day job between meetings of the set.

- Classically, an action learning set will have a facilitator whose job is to help people get to grips with the method and then to help the group stick to the method.

If you want to learn a little bit more about action learning sets, there's a great briefing here, from BOND who do a great job building capacity in UK-based development NGOs.

A debriefing group

A different approach which has some of the same benefits might be a ‘debriefing group’. This is not a recognised ‘thing’ in the same way that an action learning set it. I’ve made the term up! This particular client organisation is global, so getting people together face to face is a big deal. Even finding a suitable time for a telecon that works for all time zones is a challenge. So I came up with this idea:

- A regular slot, say monthly, for a telecon or other virtual meeting.

- The meeting would last for an hour, give or take.

- The times would vary so that over the course of a year, everyone around the world has access to some timeslots which are convenient for them.

- One person volunteers to be in the spotlight for each meeting. They may have completed a successful piece of work, or indeed they may be stuck at the start or part-way through.

- They tell their story, good and bad, and draw out what they think the unresolved dilemmas or key learning points are.

- The rest of the group then get to ask questions – both for their own curiosity / clarification, and to help illuminate the situation. The volunteer responds.

- As with the action learning set, if the volunteer requests it, the group can also offer information and suggestions.

- People could choose to make notes of the key points for wider sharing afterwards, but this needs to be done in a careful way so as to not affect the essentially trusting and open space for the free discussion and learning to emerge.

- Likewise, people need to know that they won’t be judged or evaluated from these meetings – they are safe spaces where they can explore freely and share failures as well as a successes.

- Someone would need to organise each meeting (fix the time, invite people, send round reminders and joining instructions, identify the volunteer and help them understand the purpose / brief, and manage the conversation). This could be one person or a small team, and once people understand the process it could be a different person or team each time.

For peer learning, not for making decisions

Neither approach is a ‘decision making’ forum, and neither approach is about developing case studies: they are focused on the immediate learning of the people who are in the conversation, and the insight and learning comes from what the people in the group already know (even if they don’t realise that they know it). In that sense they are 100% tailored to the learners’ needs and they are also incredibly flexible and responsive to the challenges and circumstances that unfold over time.

It's success, Jim, but not as we know it: sixth characteristic

It's a marathon not a sprint: fifth characteristic of collaboration

Collaboration requires high-quality internal working : fourth characteristic

Sometimes we're drawn to the idea of collaborating because we are finding our colleagues impossible! If this is your secret motivation, I have bad news: successful collaboration requires high-quality internal working in each of the collaborating organisations.

So you need to find a way of working with those impossible colleagues too.

Why?