When I first wrote this post (20th September), we were waiting for Rishi Sunak to make his speech widely trailed as watering down or delaying UK action on reducing climate-changing emissions. As I repurpose it for this blog, his speech about limiting local authorities’ powers to make streets safer for pedestrians and cyclists is being anticipated. Progress towards net zero is being seen by some in the Conservative Party as a 'wedge' issue in the run up to the next general election, despite polling showing solid cross-party support. But there is something going on: an understandable fear of unfairness or incompetence in policies to reduce emissions, fuelled by deliberate, cynical misinformation. How can governments (whether supra-national, national, regional or local) engage the public better on this issue?

A matrix to have up your sleeve

Seeing a familiar face, even if it's behind a mask

"You have no authority here, Jackie Weaver!" Where does 'authority' come from, in meetings?

The UK has been captivated in last few days by a viral video of highlights from a meeting of Handforth Parish Council, and Jackie Weaver has become something of a hero: the 'grown up' in the room. One participant in the Zoom meeting declared "you have no authority here Jackie Weaver!" shortly before being removed from the meeting. Where does 'authority' in a meeting come from?

A big picture take on strategic stakeholder engagement

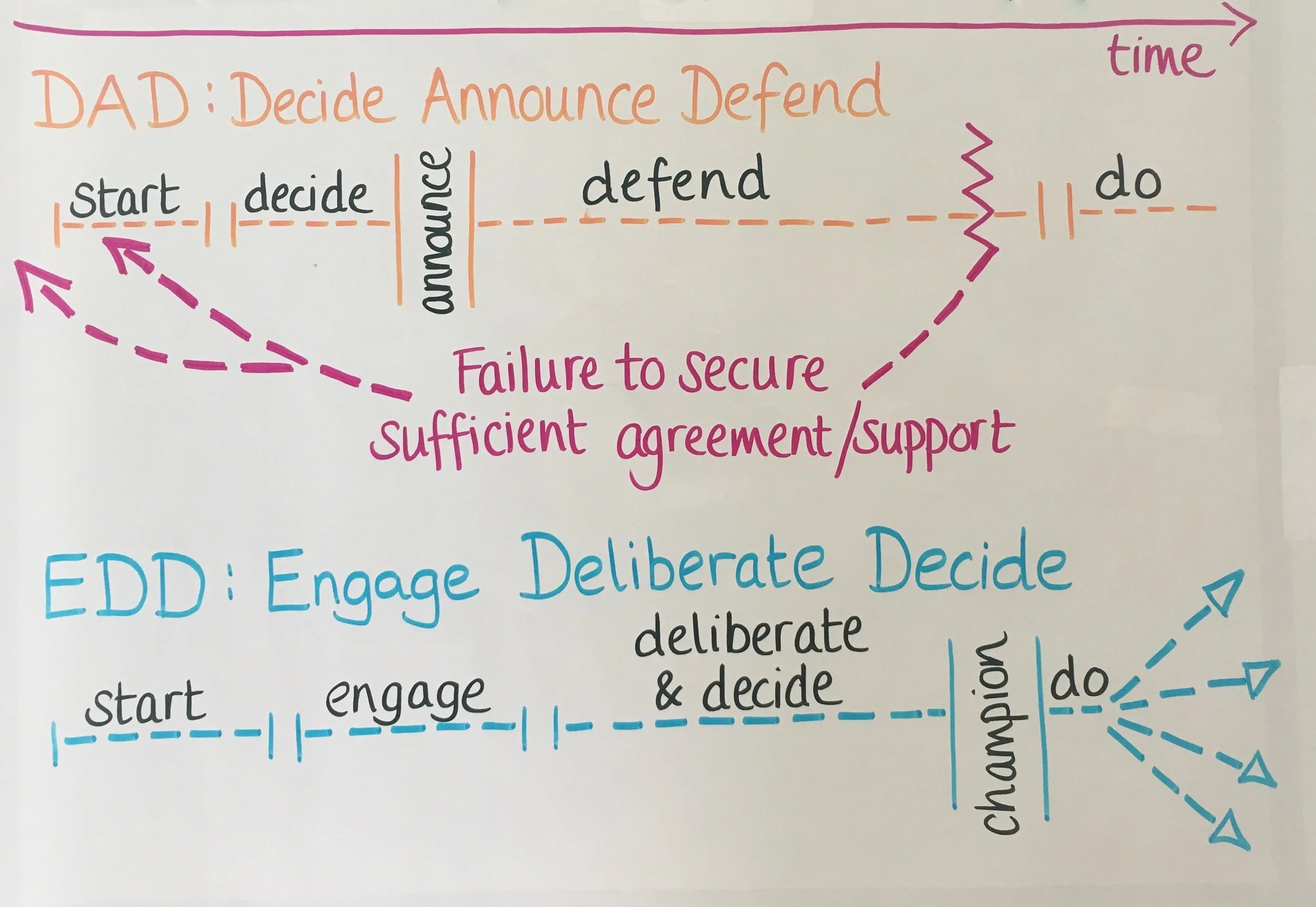

DAD and EDD: two approaches to engaging stakeholders in decisions

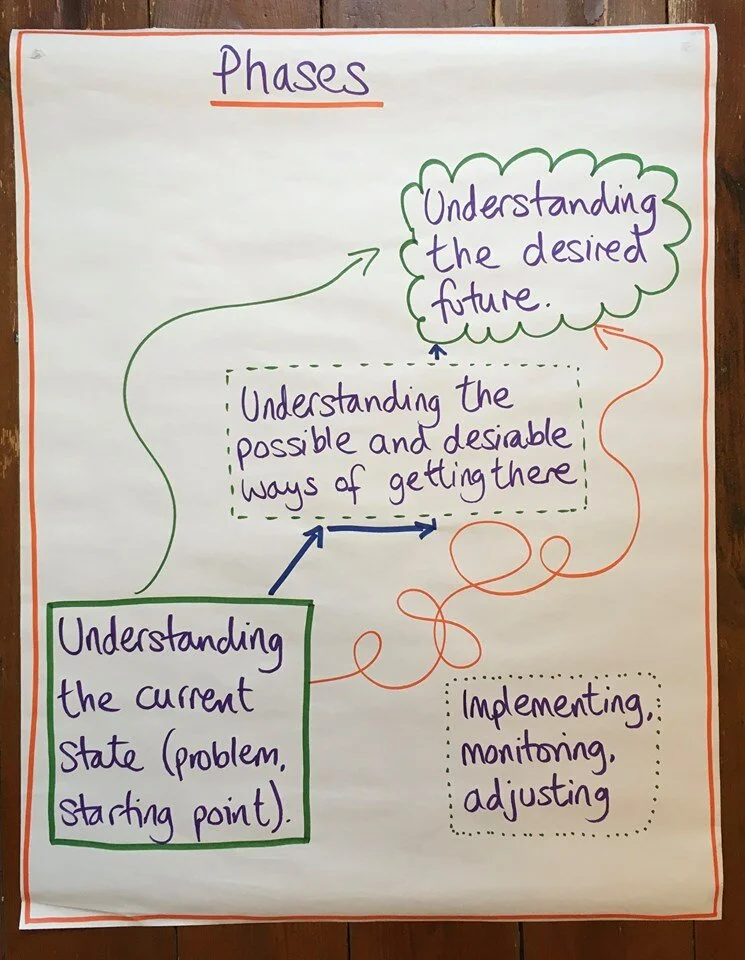

When an organisation has to make a decision, when is the best time to engage stakeholders about the best option?

If you only ask people what they think when you’ve already made up your mind, you’re taking a big risk. Here’s a quick introduction to Decide-Announce-Defend (Abandon), and its more enlightened cousin Engage-Deliberate-Decide.

What is a Citizens' Assembly?

Citizens’ Assemblies are having a bit of a moment in the UK, with Extinction Rebellion calling for them, and national governments, parliaments and local authorities commissioning them on subjects including the future of social care, air quality, transport and climate change. But what exactly is a Citizens’ Assembly?

Powerful tools for stakeholder engagement

For your comfort and safety, webcasting is in use during this workshop

As a participation professional who’s been lurking around NHS Citizen as it develops, one of the most exciting aspects has been the webcasting. Even the debriefing team meeting at the end of the NHS Citizen Design Workshop in January this year (2015) was webcast. This is a level of openness and commitment to transparent reflection that goes way beyond anything I’ve been involved with before. I fell in love with NHS Citizen as I watched that.

On the other hand, when I was sitting down to design the detail of the particular event I was brought in to facilitate - the Citizens’ Jury test in Hatfield on 3rd and 4th March 2015 - I had some reservations.

Peer learning workshops - some emerging ideas

I'm excited about ideas for peer learning workshops that have been bubbling away in my head and are beginning to take shape.

Focused, coachy, peer learning

I want to bring together sustainability people of various kinds, to be able to talk with each other about their challenges and ideas in a more expansive and easeful way than a conference allows.

People really benefit from being able to think aloud in coaching conversations. I've seen the transformations that can happen when supportive challenge prompts a new way of looking at things.

We also get so much from comparing our own experiences with peers: finding the common threads in individual contexts, exploring ideas about ways forward.

I’d like to combine these things by making the peer learning available in smaller groups and smaller chunks, where the atmosphere is more like coaching.

What's the idea?

The idea is to run half-day workshops, with between 6 and 10 people at each event. The intention is that they are safe and supporting spaces, where people can talk freely. We'll meet in spaces that are relaxed, creative, private, energising and feel good to be in. (More comfortable than the stone steps in the picture.)

Each workshop would have a theme, to help focus the conversations and make sure people who come along have enough in common for those conversations to be highly productive.

I'd run a few, on different themes, and people can come to one, some or all of them. They don't have to come to them all, so the mix of people will be different for each workshop.

I'd charge fees, probably tiered pricing so that it's affordable for individuals and smaller not-for-profits, but commercial prices for bigger and for-profit organisations.

The content of each workshop will come from the participants, rather than me: my role is to facilitate the conversations, rather than to teach or train people.

Choices, dilemmas, testing

When I've tested this idea with a few people, many have said that the success of the workshops will depend on who else is there: people with experience, insight, credibility. People they feel able to trust, before they commit to booking. I think this is useful feedback.

On the other hand, I'm unsure about the best way to ensure this. Is it enough to include a description of "who these workshops are for" and leave it to people to decide for themselves? Or should I set up an application process of some kind: asking people who apply to include a short explanation of who they are, what their role and experience is, and why they want to come along.

If I set up an 'application' process, will that be off-putting to the naturally modest? Too cumbersome? Adding extra steps (apply, wait, get place confirmed, then pay...) feels risky: at each step, the pool of likely participants will get smaller. Will this make the workshops unviable? Who am I to choose, anyway?

Another option is to make the workshops 'by invitation' with people having the option of requesting an invitation for their friends, peers, colleagues - or even themselves. This is what I'm leaning towards at the moment, based on gut feel.

Will this increase people's confidence in the workshops - that not just anyone gets a place, their peers will provide quality reflections and be people worth meeting? Will it make those people who do get an invitation feel special, better about themselves?

And will I really turn down anyone who asks for an invitation? What will they feel?

I've set up a survey to gather views on this, as well as on the topics that will be most interesting to people. Please let me know here where's there a short survey. Discounts and prizes available!

How it feels to experiment

I'm not a natural entrepreneur. Some people love to experiment and learn from failure. Fail faster. Fail cheaper. Intellectually I'm committed to experimenting with these workshops: testing out ideas about formats, marketing, pricing, venues, topic focus vs emergence, length, the amount of 'taught' content vs 'created' content and so on.

Emotionally: not so much. I want to get everything right before I start (which is why it's taken me about six months to even get to this stage). I'm getting great support from lots of people, and boy do I need it. Even sitting here, I can feel the prickly, clammy, cold physical manifestations of the fear of failure.

I need to move through the fear and into the phase of actually running some test workshops. I know they'll be great. I can see the smiles, feel the warmth, visualise the kind of room we're meeting in and the I already have the design and process clear. I have a shelf of simple but beautiful props in my office. I am 100% confident about the events themselves, it's the communications and administration of the marketing that freaks me out.

Learning from the learning

So already I'm learning. About myself, about what people say they need, about how venues can be welcoming or off-putting, about how generous people are with their time and feedback.

What are your 'engagement aims'?

Three purposes of engagement - the engagement triangle

I love helping teams plan their engagement at an early stage of their thinking. It's often done in a workshop, and we end up with an excellently solid shared understanding of what their engagement process is for, which then guide choices about methods, sequencing, aims for individual elements of the process and which stakeholders to engage.

One of the hardest disciplines to stick to - and yet one of the most useful - is to get really clear about the (multiple) engagement aims.

Sometimes known as the Public Engagement Triangle, this way of understanding "engagement aims" was developed originally by Lindsey Colbourne as part of her work with the Sciencewise-ERC, for the Science for All Follow Up Group.

The triangle helps the team get clear about:

- What they need to transmit to people outside the team - more everyday words like 'tell', 'educate', 'raise awareness', 'inspire', 'persuade' also fit under this heading.

- What they need to receive from people outside the team - 'ask', 'insight', 'research' which might include both objective facts and opinion or preferences.

- What they need to collaborate with people outside the team, to 'create', 'decide', 'agree', 'develop'.

There are a few more things to note about engagement aims.

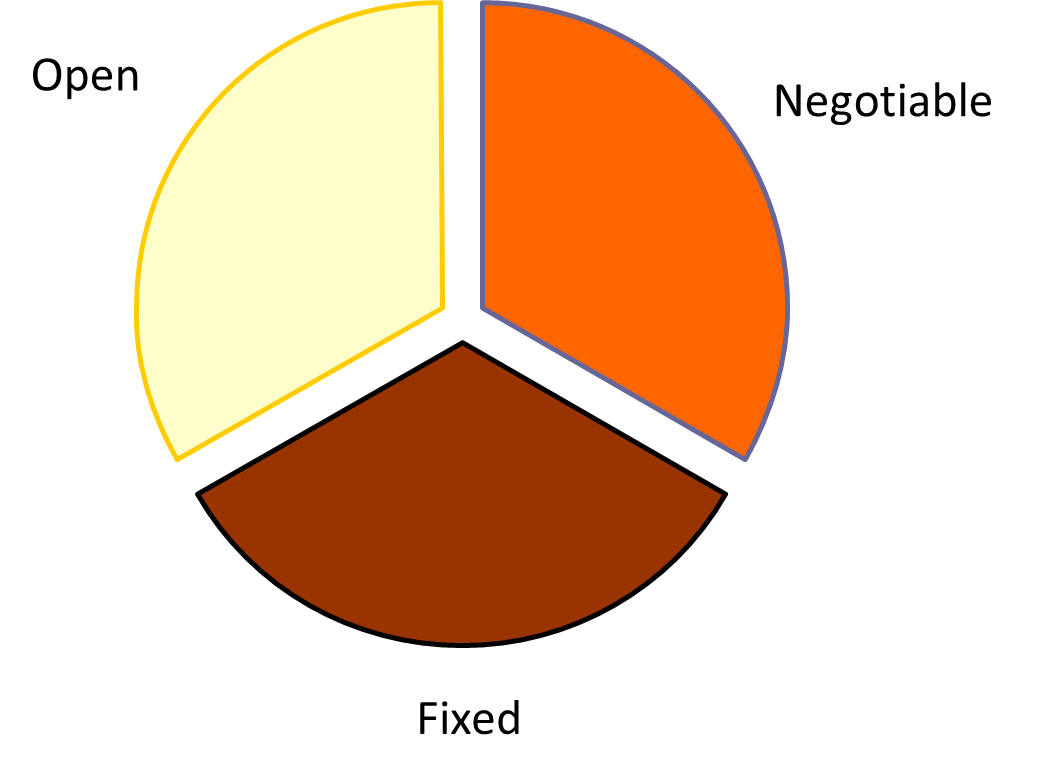

Aligned with "what's up for grabs"

Engagement aims should align seamlessly with "what's up for grabs": if you've really already decided there will be a new range of water-efficiency equipment in your stores, don't ask people whether you should start selling it. Tell them you are going to. Ask them what would make the range successful, or collaborate with them to co-design a promotional partnership.

If you have preferences about the range (price points, supplier's sustainability credentials) then tell people about these so that their responses can take appropriate account of those criteria.

If you are entirely open-minded about some aspects, then people can have free rein to come up with ideas.

Be clear who is deciding what

If you are asking people for information, ideas, options and so on, make sure that you tell them who is making the final decision, or how it will be made. People very often mistake consultation (a receive activity) for shared decision-making (which sits in the collaborate corner).

Voting in a local council election is shared decision-making: the number of votes completely determines who wins the seat. Consultation on a planning application gives members of the public an opportunity to voice their perspective, elected councillors may take those views into account when determining the application. Once the decision has been made, the planning authority will then tell people what the decision is.

In particular people interpret mechanisms which look like voting, as meaning that decision-making power has been devolved. Hence the grumpiness about Boaty McBoatface.

Consensus is a way of reaching a decision in a collaborative setting (although it is not the only one). If you are receiving views (and then making the decision yourself) then, while it can be interesting to discover areas of consensus, it is not essential. Understanding the range of views (and the needs and concerns that underlie them) can be as useful.

The aims will change as the process unfolds

Just as the things which are fixed, negotiable and open will change over time, so will the engagement aims. During an option-creating phase, things are likely to be more collaborative as people co-create possibilities. You are also likely to want to receive a wide range of views and information. Once options have been identified, then preferences and feedback are useful, but you may not want to encourage people to come up with entirely new options. (Of course, if none of your options are acceptable, you may well need to to do this. In effect you will be going back to being open, rather than having negotiable options.) And when you've decided on a fixed outcome, tell people.

Aims for individual activities within the wider process

Some activities are brilliantly suited to tell aims, others to ask aims and some to collaborate aims. A feedback form on a newsletter is unlikely to elicit a well-worked up option supported by multiple parties. A focus group isn't a good way of getting your message out.

Here's a table of appropriate techniques.

Engagement methods and the kinds of aims they are most suited to

Aims for different stakeholders

Depending on the kind of 'stake' they have, you will want to engage different stakeholders with different levels of intensity and it's highly likely that you will have different engagement aims for different stakeholders or types of stakeholder.

When developing a strategic flood plan, for example, you may want to tell residents and people who work in a particular area that the plan is being developed, how they can keep informed about its progress, what their opportunities are to input and in due course, what you have decided.

You will want to ask landowners, parish and town councillors and those people managing particular businesses, nature reserve, utilities and vital services what their aspirations and needs are over the time period of the plan, and for data about geology, biodiversity, demographics and so on.

And you will want to collaborate with key decision-makers whose support and active involvement is vital for the success of the strategy - e.g. county council, lead local flood authority and so on.

Plan and improvise

This kind of strategic, analytical approach shouldn't be seen as a way of tying you down. The engagement plan should be a living thing: not sitting on a shelf gathering dust. In fact, it gives the team a great foundation of shared understanding of the context and objectives which makes improvising in response to changing circumstances much more successful.

Boaty McBoatface and public engagement

First, an apology. I am going to try to make some serious points here and it may make you groan. Taking all the fun away. Sorry about that.

Second, a confession. I LOVE Boaty McBoatface.

However.

Let's take this from the top. What were NERC's engagement aims? My guess is that the main aim was to 'transmit' the message that NERC does amazing research in the polar regions and that they are getting a new boat. The #NameOurShip campaign has certainly done that. Perhaps they had a secondary 'receive' aim - gathering contact details for people who are interested, or gathering a long-list of names. Since the decision-making power for the actual name does not rest with the public (NERC's press release today says: "NERC will now review all of the suggested names and the final decision for the name will be announced in due course"), the 'collaborate' aim is confined to expressing a preference about the names.

And what's up for grabs? Their rather lovely public website doesn't seem to have a page about the 'rules', so I'm guessing here. Fixed: there will be a boat, it will have a name, NERC will decide the name. Presumably there are some criteria, explicit or implicit. I couldn't find these. I'm guessing there will be some kind of criterion to do with appropriateness, relevance or gravitas which will mean that sadly, RSS Boaty McBoatface will not be painted on the side of this noble vessel. Open: the public can suggest names and express preferences about the names suggested by others. Negotiable: Hmm, nothing really.

So, what went wrong? You might argue, nothing at all - thousands of names were submitted and many more preferences expressed. NERC now has a global audience of people keen to hear the announcement and with some interest in the ship and its work.

This is an engagement process leading to a decision with very low jeopardy. Very few people will be impacted 'highly' by the decision. If the decision were of a different kind - whether or not to change the flood defences in a particular area, for example, or site a geological disposal facility for radioactive waste - then being confused about who is taking which decisions and what their criteria are could lead to anger and conflict.

In my experience, people haven't often reflected on the subtleties of the difference between consultation and shared decision-making, and can assume that a 'voting' mechanism is always a decision-making mechanism. Thinking you are deciding, and then realising you're just being canvassed, can lead to grumpiness. Client teams also sometimes need help coming to a shared view about what the decision-making points are, and who decides, when they put together their engagement plan.

Which is why it's a good idea to be very clear about the process aspects of your engagement:

- What are your engagement aims?

- What's up for grabs?

- Who the stakeholders are, their level of influence and the level of impact the decision will have on them.

- Who is taking which decisions, and on the basis of what criteria?

It's a shame that NERC's process isn't really devolved decision-making. I'd love to see cutting edge science done from the deck of RSS Boaty McBoatface. Perhaps the ship's cat can blog with the pen name Boaty McBoatface. I'd read that.

Update

[6th May 2016]

NERC has announced that it will call the ship the RSS Sir David Attenborough. A great name: Sir David is a bona fide national treasure, and has taught successive generations about the wonder, diversity and jaw-dropping bonkersness of life of this astonishing planet of ours. But still people, including the BBC, are describing the public engagement as a 'vote' (implying decision-making has been devolved) rather than a long-listing or a canvassing of support. And the House of Commons Science and Technology Committee, which is looking into science communication, are likely to question Professor Duncan Wingham about the initiative.

They didn't take up my suggestion of the ship's cat: they've gone for the even better choice of naming an undersea remote yellow submarine Boaty McBoatface . Which I think is a great way to acknowledge the public's input and maintain the interest.

InterAct Networks - thank you for a wonderful ride

For over fifteen years, InterAct Networks worked to put stakeholder and public engagement at the heart of public sector decision-making, especially through focusing on capacity-building in the UK public sector. This work - through training and other ways of helping people learn, and through helping clients thinks about structures, policies and organisational change - helped organisations get better at strategically engaging with their stakeholders to understand their needs and preferences, get better informed, collaboratively design solutions and put them into practice. Much of that work has been with the Environment Agency, running the largest capacity-building programme of its kind.

History

InterAct Networks was registered as a Limited Liability Partnership in February 2002.

Founding partners Jeff Bishop, Lindsey Colbourne, Richard Harris and Lynn Wetenhall established InterAct Networks to support the development of 'local facilitator networks' of people wanting to develop facilitation skills from a range of organisations in a locality.

These geographically based networks enabled cross organisational learning and support. Networks were established across the UK, ranging from the Highlands and Islands to Surrey, Gwynedd to Gloucestershire. InterAct Networks provided the initial facilitation training to the networks, and supported them in establishing ongoing learning platforms. We also helped to network the networks, sharing resources and insights across the UK. Although some networks (e.g. Gwynedd) continue today, others found the lack of a 'lead' organisation meant that the network eventually lost direction.

In 2006, following a review of the effectiveness of the geographical networks, InterAct Networks began working with clients to build their organisational capacity to engage with stakeholders (including communities and the public) in decision making. This work included designing and delivering training (and other learning interventions), as well as setting up and supporting internal networks of engagement mentors and facilitators. We have since worked with the Countryside Council for Wales, the UK Sustainable Development Commission, Defra, DECC (via Sciencewise-ERC see p10), Natural England and primarily the Environment Agency in England and Wales.

Through our work with these organisations InterAct Networks led the field in:

diagnostics

guidance

tools and materials

new forms of organisational learning.

After Richard and Jeff left, Penny Walker joined Lindsey and Lynn as a partner in 2011, and InterAct Networks became limited company in 2012. In 2014, Lynn Wetenhall retired as a Director.

Some insights into building organisational capacity

Through our work with clients, especially the Environment Agency, we have learnt a lot about what works if you want to build an organisation's capacity to engage stakeholders and to collaborate. There is, of course, much more than can be summarised here. Here are just five key insights:

- Tailor the intervention to the part of the organisation you are working with.

- For strategic, conceptual 'content', classroom training can rarely do more than raise awareness.

- Use trainers who are practitioners.

- Begin with the change you want to see.

- Learning interventions are only a small part of building capacity.

Tailor the intervention

An organisation which wants to improve its engagement with stakeholders and the public in the development and delivery of public policy needs capacity at organisational, team and individual levels.

This diagram, originated by Jeff Bishop, shows a cross-organisational framework, helping you to understand the levels and their roles (vision and direction; process management; delivery). If capacity building remains in the process management and delivery zones, stakeholder and public engagement will be limited to pockets of good practice.

Classroom training will raise awareness of tools

There are half a dozen brilliant tools, frameworks and concepts which are enormously helpful in planning and delivering stakeholder and public engagement. Classroom training (and online self-guided learning) can do the job of raising awareness of these. But translating knowledge into lived practice - which is the goal - needs ongoing on-the-job interventions like mentoring, team learning or action learning sets. Modelling by someone who knows how to use the tools, support in using them - however inexpertly at first - and reinforcement of their usefulness. Reflection on how they were used and the impact they had.

Use trainers who are practitioners

People who are experienced and skillful in planning and delivering stakeholder and public engagement, and who are also experienced and skillful in designing and delivering learning interventions, make absolutely the best capacity-builders. They have credibility and a wealth of examples, they understand why the frameworks or skills which are being taught are so powerful. They understand from practice how they can be flexed and when it's a bad idea to move away from the ideal. We were enormously privileged to have a great team of practitioner-trainers to work with as part of the wider InterAct Networks family.

Begin with the change you want to see

The way to identify the "learning intervention" needed, is to begin by asking "what does the organisation need to do differently, or more of, to achieve its goals?", focusing on whatever the key challenge is that the capacity building needs to address. Once that is clear (and it may take a 'commissioning group' or quite a lot of participative research to answer that question), ask "what do (which) people need to do differently, or more of?". Having identified a target group of people, and the improvements they need to make, ask "what do these people need to learn (knowledge, skills) in order to make those improvements?". At this stage, it's also useful to ask what else they need to help them make the improvements (permission, budget, resources, changes to policies etc). Finally, ask "what are the most effective learning interventions to build that knowledge and those skills for these people?". Classroom training is only one solution, and often not the best one.

Learning interventions are (only) part of the story

Sometimes the capacity that needs building is skills and knowledge - things you can learn. So learning interventions (training, coaching, mentoring etc) are appropriate responses. Sometimes the capacity "gap" is about incentives, policies, processes or less tangible cultural things. In which case other interventions will be needed. The change journey needs exquisite awareness of what 'good' looks like, what people are doing and the impact it's having, what the progress and stuckness is. Being able to share observations and insights as a team (made up of both clients and consultants) is invaluable.

The most useful concepts and frameworks

Over the years, some concepts and frameworks emerged as the most useful in helping people to see stakeholder engagement, collaboration and participation in a new light and turn that enlightenment into a practical approach.

I've blogged about some of these elsewhere on this site: follow the links.

- What's up for grabs? What's fixed, open or negotiable.

- Asking questions in order to uncover latent consensus - the PIN concept.

- How much engagement? Depending on the context for your decision, project or programme, different intensities of engagement are appropriate. This tool helps you decide.

- Is collaboration appropriate for this desired outcome? This matrix takes the 'outcome' that you want to achieve as a starting point, and helps you see whether collaborating with others will help you achieve it.

- Engagement aims: transmit, receive and collaborate. Sometimes known as the Public Engagement Triangle, this way of understanding "engagement aims" was developed originally by Lindsey Colbourne as part of her work with the Sciencewise-ERC, for the Science for All Follow Up Group.

- Who shall we engage and how intensely? (stakeholder identification and mapping)

Three-day facilitation training

As part of this wider suite of strategic and skills-based capacity building, InterAct Networks ran dozens of three-day facilitation skills training courses and helped the Environment Agency to set up an internal facilitator network so that quasi-third parties can facilitate meetings as part of public and stakeholder engagement. The facilitator network often works with external independent facilitators, contracted by the Environment Agency for bigger, more complex or higher-conflict work. This facilitation course is now under the stewardship of 3KQ.

More reports and resources

Here are some other reports and resources developed by the InterAct Networks team, sometimes while wearing other hats.

Evaluation of the use of Working with Others - Building Trust for the Shaldon Flood Risk Project, Straw E. and Colbourne, L., March 2009.

Departmental Dialogue Index - developed by Lindsey Colbourne for Sciencewise.

Doing an organisational stocktake.

Organisational Learning and Change for Public Engagement, Colbourne, L., 2010, for NCCPE and The Science for All group, as part of The Department of Business, Innovation and Skills (BIS)’ Science and Society programme.

Mainstreaming collaboration with communities and stakeholders for FCERM, Colbourne, L., 2009 for Defra and the Environment Agency.

Thank you for a wonderful ride

In 2015, Lindsey and Penny decided to close the company, in order to pursue other interests. Lindsey's amazing art work can be seen here. Penny continues to help clients get better at stakeholder engagement, including through being an Associate of 3KQ, which has taken ownership of the core facilitation training course that InterAct Networks developed and has honed over the years. The Environment Agency continues to espouse its "Working with Others" approach, with great guidance and passion from Dr. Cath Brooks and others. Colleagues and collaborators in the work with the Environment Agency included Involve and Collingwood Environmental Planning, as well as Helena Poldervaart who led on a range of Effective Conversations courses. We hope that we have left a legacy of hundreds of people who understand and are committed to asking great questions and listening really well to the communities and interests they serve, for the good of us all.

Environmental justice - from Kendal to Kiribati

The justice thread continues. We were invited to think about environmental justice. Is environmental concern the privilege of those who don’t have to worry about oppression, poverty and the daily grind? Or are environmental problems yet another way in which the privileged dump on the poor?

And who gets to ask and answer these questions?

The questions drew me back to connections between justice and climate change, and my own role as a facilitator of public and stakeholder engagement.

Climate change is having a disproportionate effect on the poorest people in the poorest countries

A few years ago I was lucky enough to be invited to facilitate a two-day workshop for human rights lawyers and climate activists. I’ve blogged about a process aspect of that event here.

I met Maria Tiimon there. She’s from Kiribati - one of those stunningly beautiful Pacific nations that cartoons of desert islands are based on. All coconut trees, blue skies and silver sand.

Pic by Nick Hobgood on flikr, creative commons.

But it won’t be for long. Here’s Anote Tong, President of the Republic of Kiribati, addressing the 106th session of the Council of the International Organisation for Migration (IOM).

Why the IOM? Because it seems likely that migration is the future for Kiribati. President Tong said in 2013 "For our people to survive, then they will have to migrate. Either we can wait for the time when we have to move people en masse or we can prepare them—beginning from now ..."

Andrew Teem is the senior policy advisor on climate change to the Kiribati government. See him interviewed here.

When people talk about climate justice, it’s forced migration and the creation of refugees due to extreme weather and chronic climatic changes that they have in mind.

It’s not just small island states. Another country where people are suffering now is Bangladesh.

The Environmental Justice Foundation has gathered witness testimony and data showing how flooding is displacing farmers. EJF talks about “significant damage to vital infrastructure, widespread devastation to housing, reduced access to fresh water for drinking, sanitation and irrigation, and rising poverty and hunger caused by increasingly extreme weather events and the gradual but sustained deterioration in environmental security”.

Establishing that the impacts of climate change have a human rights dimension was very important to this group of lawyers, and the idea is gaining traction.

Poorer people are hit harder

Closer to home, the UK has been inundated by flooding, likely to be caused by extreme weather exacerbated by climate change.

Over the last five years, much of my stakeholder engagement work has been on UK flooding and the best ways to reduce the risks to people from flood events.

There are a couple of distinct “justice” issues here, which come up in workshops and public meetings, and add to the emotional heat.

One is that people who are already disadvantaged (poorer, disabled or caring for small children) tend to suffer most when there is a flood and find it harder to get back on their feet. It could be as simple as not having insurance like some people in Kendal, or a car to transport you to a safe place, or savings to tide you over so you don’t have to get a loan at sky-high interest.

The Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF) has done a lot of work on this. They say that people's vulnerability to the impacts of climate change is mode worse by “income inequalities, social networks and social characteristics of neighbourhoods."

In the case of heatwaves, social factors include: social isolation; loss of public spaces; fear of crime, which leaves people unwilling to leave their homes or open their windows; and inflexible institutional regimes and the lack of personal independence in nursing homes. A variety of social factors affect the capacity of households to prepare for, respond to and recover from flooding. Low-income households are less able to make their property resilient, and to respond to and recover from the impacts of floods. The ability to relocate is affected by wealth; so also is the ability to take out insurance against flood damage. Social networks affect the ability of residents to respond to flooding – for example, through providing social supports.”

Elsewhere, JRF says:

“A mix of socioeconomic and geographical factors also create spatial distributions of vulnerability: lower-income groups living in poorer-quality housing in coastal locations are disproportionately affected by coastal flooding, while disadvantaged groups living in urban areas with the least green space are more vulnerable to pluvial flooding (flooding caused by rainfall) and heatwaves.

Tenants are more vulnerable than owner occupiers because they cannot modify their homes, so are less able to prepare for and recover from climate events.”

The second kind of justice is the “just deserts” aspect. “The wealthiest 10 per cent of households are responsible for 16 per cent of UK household and personal transport emissions, while the poorest 10 per cent are responsible for just 5 per cent.” Also according to the JRF. It’s not just ironic, it’s unjust. Like the people of Kiribati and Bangladesh, in the UK it’s the historically low-emitters of greenhouse gases who are getting the harshest impacts of climate change.

Who goes to public meetings?

Another aspect of (environmental) justice which people in my field can’t ignore - although the solutions are hard to find - is the unequal access to decision-making or decision-influencing processes like consultations or public meetings about environmental questions like transport strategies, pollution, waste, development, flood defences, emergency planning for extreme events, protection of wildlife and wild places.

I’d like to find out more about this (your comments with links to demographic studies are welcome). What are the demographic patterns and what are the effective ways of engaging people who are typically less likely to be engaged? In my partial and anecdotal experience, public meetings or community workshops during the working day are most likely to be attended by retired people, ex-professionals with a high level of confidence in and familiarity with formal decision-making processes. Whatever time of day the meeting, people with caring responsibilities (who are more likely to be women) are less able to come along. People working three part-time jobs to get by? I’d be surprised.

As public bodies embrace social media and the “digital first” approach, a new set of people may be engaged (at a guess, younger, busier) but another set (older, poorer, with less access to e-communications) are systematically excluded.

It’s the responsibility of those who are convening the engagement, to notice these patterns and make efforts to hear the perspectives and preferences of those who seem to have been unwittingly excluded. To do otherwise would be unjust.

Some lessons from Citizens Juries enquiring into onshore wind in Scotland

I've been reading "Involving communities in deliberation: A study of 3 citizens’ juries on onshore wind farms in Scotland" by Dr. Jennifer Roberts (University of Strathclyde) and Dr. Oliver Escobar (University of Edinburgh), published in May 2015.

This is a long, detailed report with lots of great facilitation and public participation geekery in it. I've picked out some things that stood out for me and that I'm able to contrast or build on from my own (limited) experience of facilitating a Citizens' Jury. But there are plenty more insights so do read it for yourself.

I've stuck to points about the Citizen Jury process - if you're looking for insights into onshore wind in Scotland, you won't find them in this blog post!

What are Citizens' Juries for?

This report takes as an underlying assumption that its focus - and a key purpose of deliberation - is learning and opinion change, which will then influence the policies and decisions of others. The jury is not seen as "an actual decision making process" p 19

"Then ... the organisers feed the outputs into the relevant policy and/or decision making processes." p4

In the test of a Citizens’ Jury that I helped run for NHS Citizen, there was quite a different mandate being piloted. The idea is that when the Citizens’ Jury is run ‘for real’ in NHS Citizen, it will decide the agenda items for a forthcoming Board Meeting of NHS England.

This is a critical distinction, and anyone commissioning a Citizens’ Jury needs to be very clear what the Jury is empowered to decide (if anything) and what it is being asked for its views, opinions or preferences on. In the latter case, the Citizens’ Jury becomes essentially a sophisticated form of consultation.

This is not necessarily a bad thing, but it needs to be very clear from the start which type of involvement is being sought.

Having confidence in the Citizens’ Jury process

To be a useful consultant mechanism, stakeholders and decision-makers need to have confidence in the Citizens’ Jury process. This applies even more strongly when the Jury has decision-making powers.

The organisers and commissioners need to consider how to ensure confidence in a range of things:

- the selection of jurors and witnesses,

- the design of the process (including the questions jurors are invited to consider and the scope of the conversations),

- the facilitation of conversations,

- the record made of conversations and in particular decisions or recommendation,

The juries under consideration in this report benefited from a Stewarding Board. This type of group is sometimes called a steering group or oversight group. It’s job is to ensure the actual and perceived independence of the process, by ensuring that it is acceptable to parties with quite difference agendas and perspectives. If they can agree that it’s fair, then it probably is. Chapter 3 of the report looks at this importance of the Stewarding Board, its composition and the challenging disagreements it needed to resolve in this process.

In our NHS Citizen test of the Citizens’ Jury concept, we didn’t have an equivalent structure, although we did seek advice and feedback from the wider NHS Citizen community (for example see this blog post and the comment thread) as well as from our witnesses, evaluators with experience of Citizens’ Juries. We also drew on our own insights and judgements as independent convenors and facilitators. My recommendation is that there be a steering group of some kind for future Citizens’ Juries within NHS Citizen.

What role for campaigners and activists?

The report contains some interesting reflections on the relationship between deliberative conversations in ‘mini publics’ and citizens who have chosen to become better informed and more active on an issue to the extent of becoming activists or campaigners. (Mini public is an umbrella term for any kind of “forum composed of citizens who have been randomly selected to reflect the range of demographic and attitudinal characteristics from the broader population – e.g. age, gender, income, opinion, etc.” pp3-4)

The report talks about a key feature of Citizens’ Juries being that they

“...use random selection to ensure diversity and thus “reduce the influence of elites, interest advocates and the ‘incensed and articulate’”

(The embedded quote is from Carolyn Hendriks’ 2011. The politics of public deliberation: citizen engagement and interest advocacy, Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan.)

So what is the role of the incensed and the articulate in a Citizens’ Jury? The detail of this would be decided by the steering group or equivalent, but broadly there are two roles outlined in the report: being a member of the steering group and thus helping to ensure confidence in the process; and being a witness, helping the jurors to see multiple aspects of the problem they are considering. See pp 239-240 for more on this.

Depending on the scope of the questions the Citizens’ Jury is being asked to deliberate, this could mean a very large steering group or set of witnesses. The latter would increase the length of the jury process considerably, which makes scoping the questions a pragmatic as well as a principled decision.

The project ran from April 2013 to May 2015. You can read the full report here.

Thanks very much to Clive Mitchell of Involve who tipped me off about this report.

See also my reflections on the use of webcasting for the NHS Citizen Citizens' Jury test.

Characteristics of collaborative working, episode one of six

DareMini

So DareConfMini was a bit amazing. What a day. Highlights:

- Follow your jealousy from Elizabeth McGuane

- Situational leadership for ordinary managers from Meri Williams

- The challenge of applying the great advice you give to clients, to your own work and practice from Rob Hinchcliffe

- Finding something to like about the people who wind you up the most from Chris Atherton

- Being brave enough to reveal your weaknesses from Tim Chilvers

- Jungian archetypes to help you make and stick to commitments from Gabriel Smy

- Radical challenges to management orthodoxy from Lee Bryant

- Meeting such interesting people at the after party

No doubt things will continue to churn and emerge for me as it all settles down, and I'll blog accordingly.

In the meantime, all the videos and slides can be watched here and there are some great graphic summaries here (from Francis Rowland) and here (from Elisabeth Irgens)

There are also longer posts than mine from Charlie Peverett at Neo Be Brave! Lessons from Dare and Banish the January blues – be brave and get talking from Emma Allen.

If you are inspired to go to DareConf in September, early bird with substantial discounts are available until 17th February.

Many thanks to the amazing Jonathan Kahn and Rhiannon Walton who are amazing event organisers - and it's not even their day job. They looked after speakers very well and I got to realise a childhood fantasy of dancing at Sadler's Wells. David Caines drew the pictures.

Who shall we engage, and how intensely?

So you've brainstormed a long (long!) list of all the kinds of people and organisations who have a stake in the policy, project, organisation or issue that you are focusing on. This is what we call stakeholder identification.

What do you do next?

Stakeholder analysis

Now there are lots of ways you can analyse your universe of stakeholders, but my absolute favourite, for its conceptual neatness and the way it lends itself to being done by a group, is the impact / influence matrix.

Notice the subtle but important difference between this matrix, and the one most commonly used by PR and communications specialists, which focuses on whether stakeholders are in favour of - or opposed to - your plans. It would be inappropriate to use this for stakeholder engagement which engages in order to inform decisions, because you will be engaging before you have made up your mind. And if you haven't decided yet, how can stakeholders have decided whether they agree with you?!

Instead, the matrix helps you to see who needs to be engaged most intensely because they can have a big impact on the success or otherwise of the work, or because the work will have a big impact on them. It is 'blind' to whether you think the stakeholders are broadly your mates or the forces of darkness.

Map as a team

Your list is written out on sticky notes - one per note - and the stakeholders have been made as specific as possible: Which team at the local authority? Which residents? Which NGO? Which suppliers in the supply chain?

You have posted up some flip chart paper with the matrix drawn on.

The mapping is ideally done as a team - and that team might even include some stakeholders! During the mapping, everyone needs to be alert to the risk of placing a particular stakeholder in the 'wrong' place, because you don't want to engage with them. It's self-defeating, because sooner or later you will need to engage with the most influential stakeholders whether you want to or not. And sooner is definitely better than later.

You move the notes around until you're all satisfied that you have a good enough map.

Intensity? Transmit, receive, collaborate

When the mapping is complete, then you can discuss the implications: those in the low/low quadrant probably just need to be informed about what's happening (transmit). Those in the diagonal band encompassing both the high / low quadrants need to be asked what they know, what they think and what they feel about how things are now, how they might be in the future and they ways of getting from here to there (receive). NB those in the bottom right corner - highly impacted on but not influential. Vulnerable and powerless. Pay particular attention to their views, make a big effort to hear them, and help them gain in influence if you can.

Those in the 'high/high' corner are the ones you need to work most closely with (collaborate), sharing the job of making sense of how things are now, co-creating options for the future, collaborating to make it happen. Because if they are not on board, you won't be able to design and implement the work.

Prioritise and plan

Now you are in a position to plan your engagement, knowing which stakeholders need mostly to be told, mostly to be listened to or mostly to be collaborated with.

Review and revise

Watch out for people and organisations moving over time. Very often the people in bottom right are the unorganised 'public'. They might be residents or consumers. If they get organised, or their cause is taken up by the media, a celebrity or a campaign group then their influence is likely to increase.

Those in the top left are potentially influential but unlikely to get involved because there's not so much in it for them. Your engagement plan might include helping them to see why their input is useful, and piquing their interest.

So stay alert to changes and alter your engagement plan accordingly.

How can I get them to trust me?

Trust is essential to collaborative work and makes all kinds of stakeholder engagement more fruitful. Clients often have 'increased trust' as an engagement objective. But how do you get someone to trust you?

Should they?

My first response is to challenge back: should people trust you? Are you entering this collaboration or engagement process in good faith? Do you have some motives or aims which are hidden or being spun? Do some people in your team see consultation and participation as just more sophisticated ways of persuading people to agree with what you've already made up your mind about? Or are you genuinely open to changing things as a result of hearing others' views? Is the team clear about what's up for grabs?

It's an ethical no-brainer: don't ask people to trust you if they shouldn't!

Earn trust

Assuming you do, hand on heart, deserve trust, then the best way to get people to trust you is to be trustworthy.

Do what you say you're going to do. Don't commit to things that you can't deliver.

Don't bad-mouth others - hearing you talk about someone one way in public and another in a more private setting will make people wonder what you say about them when they're not around.

Trust them

The other side of the coin is to be trusting. Show your vulnerability. Share information instead of keeping it close. Be open about your needs and constraints, the pressures on you and the things that you find hard. If you need to give bad news, do so clearly and with empathy.

Give it time

Long-term relationships require investment of time and effort. Building trust (or losing it) happens over time, as people see how you react and behave in different situations.

Be worthy of people's trust, and trust them.

Working collaboratively: world premiere!

So it's here! A mere nine months after first being contacted by Nick Bellorini of DōSustainability, my e-book on collaboration is out!

Over the next few weeks, I'll be blogging on some of the things that really struck me about writing it and that I'm still chewing over. In the meantime, I just wanted to let you know that it's out there, and you, dear reader, can get it with 15% off if you use the code PWP15 when you order it. See more here.

It's an e-book - and here's something cool for the dematerialisation and sharing economy geeks: you can rent it for 48 hours, just like a film! Since it's supposed to be a 90 minute read, that should work just fine.

Thanks!

And I couldn't have done it without the wonderful colleagues, clients, peers, critics, fellow explorers and tea-makers who helped out.

Andrew Acland, Cath Beaver, Craig Bennett, Fiona Bowles, Cath Brooks, Signe Bruun Jensen, Ken Caplan, Niamh Carey, Lindsey Colbourne, Stephanie Draper, Lindsay Evans, James Farrell, Chris Grieve, Michael Guthrie, Charlotte Millar, Paula Orr, Helena Poldervaart, Chris Pomfret, Jonathon Porritt, Keith Richards, Clare Twigger-Ross, Neil Verlander, Lynn Wetenhall; others at the Environment Agency; people who have been involved in the piloting of the Catchment Based Approach in England in particular in the Lower Lee, Tidal Thames and Brent; and others who joined in with an InterAct Networks peer learning day on collaboration.