Some people just hate shouting out ideas in a group. If you need quantity and creativity, and to make sure the quiet thinkers contribute their ideas too, this alternative to the traditional brainstorm is my new go-to technique.

Organising small groups within a larger event

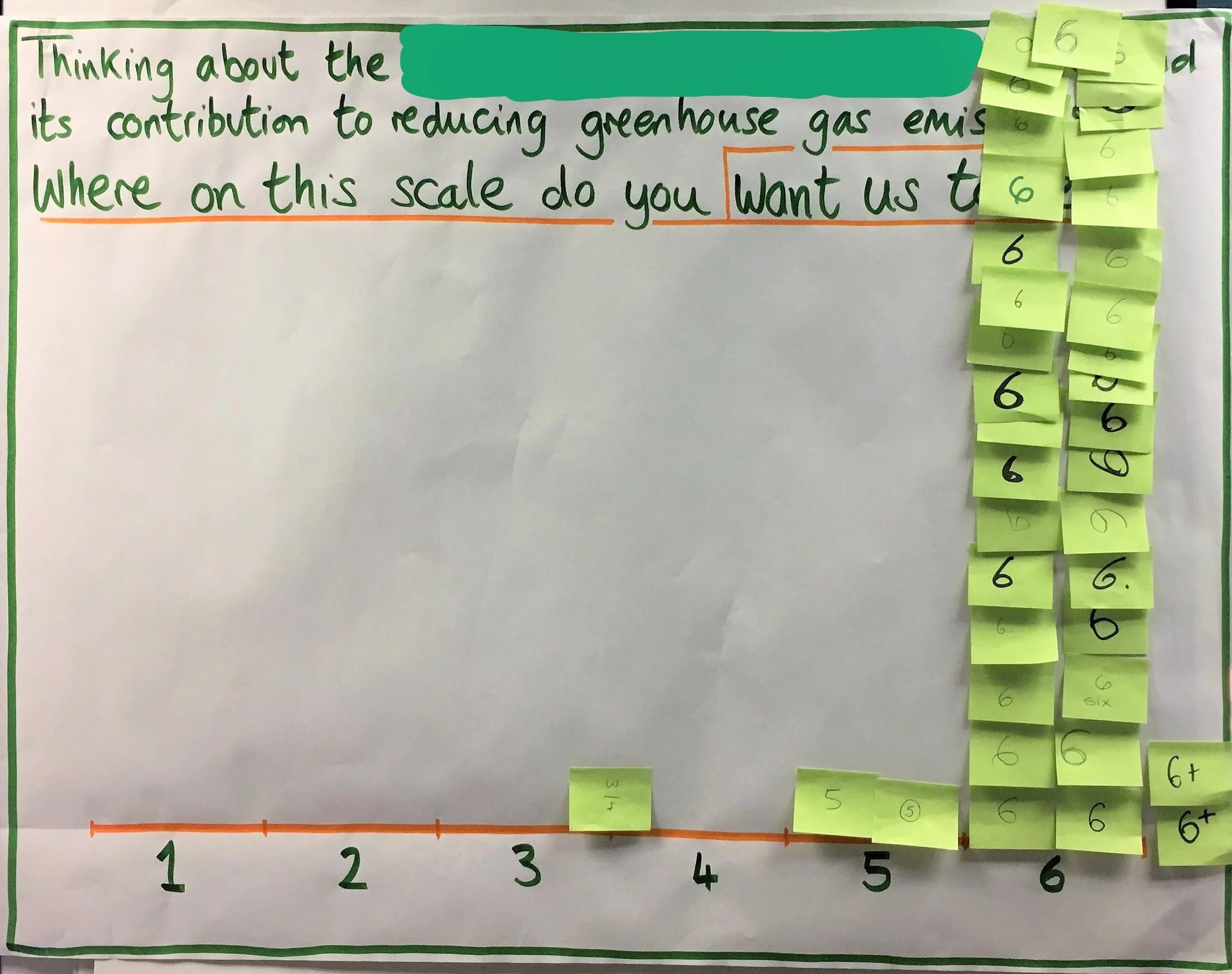

Instant bar charts: a safe snapshot of opinion

Inventing techniques and exercises

Paying attention to the mood

When I first met with Brigid Finlayson and Carolina Karlstrom, to see whether we could work together to create the first She is Still Sustainable, we talked a lot about the kind of event we wanted to make it. And our conversation focused a lot on mood, atmosphere, emotional tone: we wanted it to be “warm, safe, friendly event which is refreshing, inspiring and supportive”.

Doing the work in sustainability that we want to do

Lots of the women who came along to She is Still Sustainable said that the highlight was a co-coaching exercise we ran, using a solutions focus approach. People paired up and coached each other, asking positive, future-oriented questions about the sustainability work they wanted to do. The instructions are here.

Celebrate your achievements!

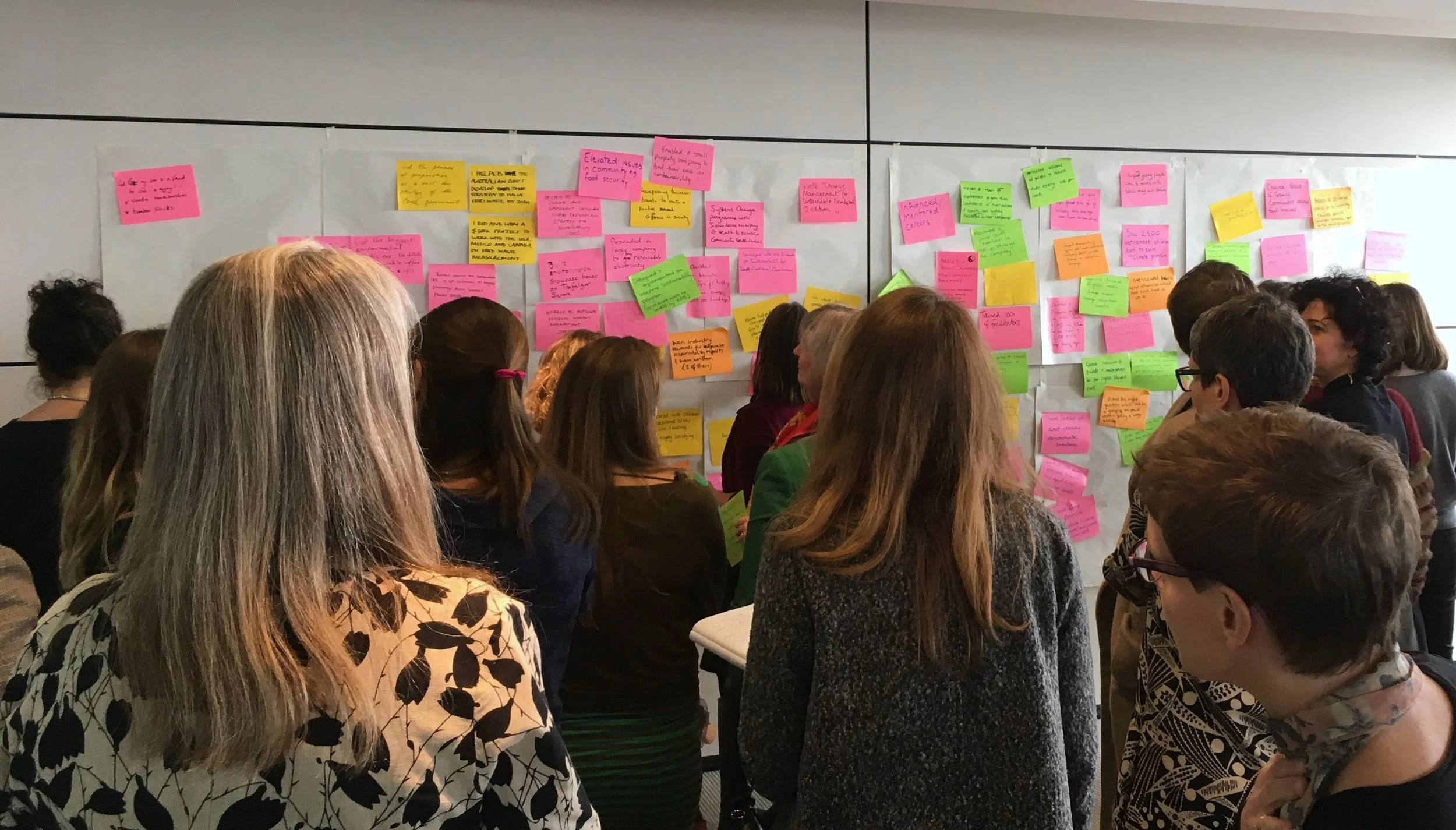

One of the lovely things that we did at She is Still Sustainable last month, was to build a wonderwall of our achievements. And wow! What a lot we have achieved.

Some were very personal – surviving divorce, arranging funerals, raising children....

Some had enormous reach – training 100s of facilitators, systems change programme with Sierra Leone Ministry of Health to improve community health, part of a team delivering a sustainable London 2012...

Carousel in action

5 minute meeting makeover

We know it shouldn’t be like this, but sometimes we find ourselves in a meeting which is ill-defined, purposeless and chaotic.

Maybe it’s been called at short notice. Maybe everyone thought someone else was doing the thinking about the agenda and aims. Maybe the organisation has a culture of always being "too busy" to pay attention to planning meetings.

For whatever reason, you’re sitting there and the conversation has somehow begun without a structured beginning.

This is the moment to use the five minute meeting makeover!

Decisions? Decisions!

This blog post pulls together some resources that I shared at a workshop last week, for people in community organisations wanting to make clear decisions that stick. Groups of volunteers can't be 'managed' in the same that a team in an organisation is managed: consensus and willingness to agree in order to move forward are more precious. Sometimes, however, that means that decisions aren't clear or don't 'stick' - people come away with different understandings of the decision, or don't think a 'real' decision has been made (just a recommendation, or a nice conversation without a conclusion). And so it's hard to move things forward.

I flagged up a number of resources that I think groups like this will find useful:

- Descriptive agendas - that give people a much clearer idea of what to expect from a meeting;

- Using decision / action grids to record the outputs from a meeting unambiguously;

- Be clear about the decision-making method (e.g. will it be by consensus, by some voting and majority margin, or one person making the decision following consultation?) and criteria.

- Understanding who needs to be involved in the run-up to a decision.

- Taking time to explore options and their pros and cons before asking people to plump for a 'position'.

Some lessons from Citizens Juries enquiring into onshore wind in Scotland

I've been reading "Involving communities in deliberation: A study of 3 citizens’ juries on onshore wind farms in Scotland" by Dr. Jennifer Roberts (University of Strathclyde) and Dr. Oliver Escobar (University of Edinburgh), published in May 2015.

This is a long, detailed report with lots of great facilitation and public participation geekery in it. I've picked out some things that stood out for me and that I'm able to contrast or build on from my own (limited) experience of facilitating a Citizens' Jury. But there are plenty more insights so do read it for yourself.

I've stuck to points about the Citizen Jury process - if you're looking for insights into onshore wind in Scotland, you won't find them in this blog post!

What are Citizens' Juries for?

This report takes as an underlying assumption that its focus - and a key purpose of deliberation - is learning and opinion change, which will then influence the policies and decisions of others. The jury is not seen as "an actual decision making process" p 19

"Then ... the organisers feed the outputs into the relevant policy and/or decision making processes." p4

In the test of a Citizens’ Jury that I helped run for NHS Citizen, there was quite a different mandate being piloted. The idea is that when the Citizens’ Jury is run ‘for real’ in NHS Citizen, it will decide the agenda items for a forthcoming Board Meeting of NHS England.

This is a critical distinction, and anyone commissioning a Citizens’ Jury needs to be very clear what the Jury is empowered to decide (if anything) and what it is being asked for its views, opinions or preferences on. In the latter case, the Citizens’ Jury becomes essentially a sophisticated form of consultation.

This is not necessarily a bad thing, but it needs to be very clear from the start which type of involvement is being sought.

Having confidence in the Citizens’ Jury process

To be a useful consultant mechanism, stakeholders and decision-makers need to have confidence in the Citizens’ Jury process. This applies even more strongly when the Jury has decision-making powers.

The organisers and commissioners need to consider how to ensure confidence in a range of things:

- the selection of jurors and witnesses,

- the design of the process (including the questions jurors are invited to consider and the scope of the conversations),

- the facilitation of conversations,

- the record made of conversations and in particular decisions or recommendation,

The juries under consideration in this report benefited from a Stewarding Board. This type of group is sometimes called a steering group or oversight group. It’s job is to ensure the actual and perceived independence of the process, by ensuring that it is acceptable to parties with quite difference agendas and perspectives. If they can agree that it’s fair, then it probably is. Chapter 3 of the report looks at this importance of the Stewarding Board, its composition and the challenging disagreements it needed to resolve in this process.

In our NHS Citizen test of the Citizens’ Jury concept, we didn’t have an equivalent structure, although we did seek advice and feedback from the wider NHS Citizen community (for example see this blog post and the comment thread) as well as from our witnesses, evaluators with experience of Citizens’ Juries. We also drew on our own insights and judgements as independent convenors and facilitators. My recommendation is that there be a steering group of some kind for future Citizens’ Juries within NHS Citizen.

What role for campaigners and activists?

The report contains some interesting reflections on the relationship between deliberative conversations in ‘mini publics’ and citizens who have chosen to become better informed and more active on an issue to the extent of becoming activists or campaigners. (Mini public is an umbrella term for any kind of “forum composed of citizens who have been randomly selected to reflect the range of demographic and attitudinal characteristics from the broader population – e.g. age, gender, income, opinion, etc.” pp3-4)

The report talks about a key feature of Citizens’ Juries being that they

“...use random selection to ensure diversity and thus “reduce the influence of elites, interest advocates and the ‘incensed and articulate’”

(The embedded quote is from Carolyn Hendriks’ 2011. The politics of public deliberation: citizen engagement and interest advocacy, Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan.)

So what is the role of the incensed and the articulate in a Citizens’ Jury? The detail of this would be decided by the steering group or equivalent, but broadly there are two roles outlined in the report: being a member of the steering group and thus helping to ensure confidence in the process; and being a witness, helping the jurors to see multiple aspects of the problem they are considering. See pp 239-240 for more on this.

Depending on the scope of the questions the Citizens’ Jury is being asked to deliberate, this could mean a very large steering group or set of witnesses. The latter would increase the length of the jury process considerably, which makes scoping the questions a pragmatic as well as a principled decision.

The project ran from April 2013 to May 2015. You can read the full report here.

Thanks very much to Clive Mitchell of Involve who tipped me off about this report.

See also my reflections on the use of webcasting for the NHS Citizen Citizens' Jury test.

Agree to differ

I'm listening to Matthew Taylor's Agree to Differ on iplayer. It's hard not to get caught up in the subject matter - in this case fracking - but I'm listening out for process.

I agree with Matthew Taylor's contention that in most media coverage of controversial topics "the protagonists spend more time attacking and caricaturing each other than they do addressing the heart of the issue". I also think that the orthodox approach, which is to set up discussion and disagreement as debate, with winners and losers and settled points of view, may be entertaining but is rarely a way of finding the best understanding.

In his own blog, Matthew writes about the origins of the radio series:

‘Imagine’ I thought ‘if we applied the kind of techniques used in mediation to shed much less heat and much more light?’ Vital to that method is requiring that the protagonists resist caricaturing each other’s position – something which immediately inflames debate – and focus instead on clarifying their own stance.

So what is the process that Matthew has followed in this refreshing radio programme?

- Matthew is cast in the role of mediator, and our mediatees in this opening episode were George Monbiot and James Woudhuysen - one in principle at least in favour of fracking, and one opposed to it.

- There was a round of introductions: personal, anecdotal and focusing on the very early inspiration rooted in childhood experience. Matthew himself didn't provide the same kind of introduction: he's facilitating the conversation, rather than joining in. This helped to humanise George and James: it's hard to take against these small boys with the mutual connections to woodpeckers (you have to listen to it!).

- Each mediatee was invited to give a short opening statement, uninterrupted. A bit like a courtroom or staged debate, but also with echoes of the uninterrupted opportunity to speak that you might have in setting up a "thinking environment".

- We were told to expect exploration of the things the protagonists disagreed about. This might seem counterintuitive: if what's being sought is agreement, how does exploring disagreement help. But wait...

- George and James were asked to summarise back the essence of each other's argument, and to find something in it that they do agree with.

- After a round of this, our mediator then summarised back what he'd heard about the remaining disagreement, and George and James had the opportunity to correct any misunderstandings in the summary. James took the opportunity a couple of times.

- At one point, Matthew sets out a ground rule, in response to James starting to say something outside the process: "The one rule we have here is that you're not allowed to say what you think George believes." Nicely done, and an interesting insight into the process being followed.

- This process was then repeated for a second area of disagreement.

- So for each key part of the topic, we heard about areas of agreement (e.g. "in favour of nuclear and renewables" and "neither of you sympathetic to NIMBYism") and we understood more precisely the remaining disagreement.

- At the end, Matthew summarised back what would characterise the most extreme positions - investing in or protesting against fracking. Which I found a bit strange as the sign-off: perhaps the demands of the medium for positions and opposition were too strong to be ignored.

Linearity in an aural medium

I wondered about the limitations of radio (or other aural-only media) in that you can only focus on one thing at a time: no post-it brainstorms or mind maps here, where all facets of a question can be presented at once. I find this very useful in face-to-face facilitation, for getting everything out on the table from all perspectives, before beginning to sort it. Does the "one-at-a-time" nature of speech reinforce the sense of opposition?

Well done Matthew Taylor for bringing a different approach to understanding a controversial question. Future episodes are on vivisection and the future of Jerusalem. Catch them on BBC Radio 4 Wednesday's at 8pm and Saturday at 10.15pm, or on the iplayer.

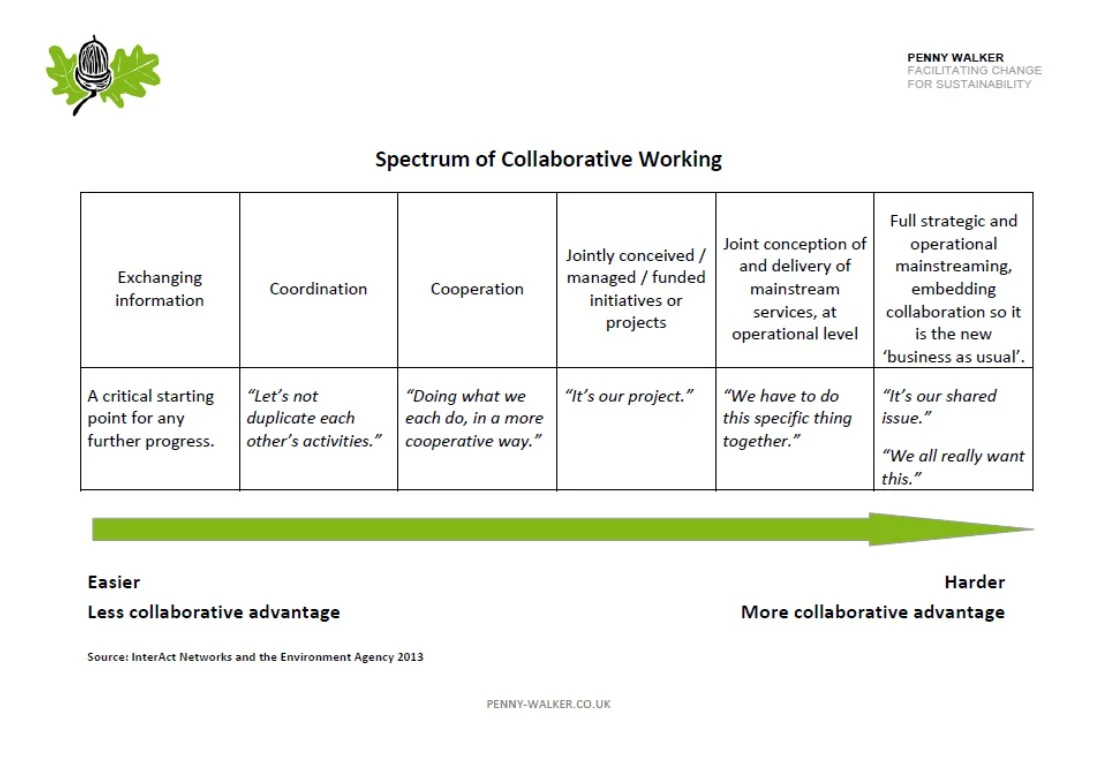

It's not all or nothing - there's a spectrum of collaborative working

Does collaboration sound like too much hard work? The examples of collaboration which get most attention are the big, the bold, the game changing.

Which can be a bit off-putting. If I collaborate, will I be expected to do something as hard and all-consuming?

Actually, most collaborative work is much more modest. And even the big and bold began as something doable.

So what kind of work might collaborators do together?

DareMini

So DareConfMini was a bit amazing. What a day. Highlights:

- Follow your jealousy from Elizabeth McGuane

- Situational leadership for ordinary managers from Meri Williams

- The challenge of applying the great advice you give to clients, to your own work and practice from Rob Hinchcliffe

- Finding something to like about the people who wind you up the most from Chris Atherton

- Being brave enough to reveal your weaknesses from Tim Chilvers

- Jungian archetypes to help you make and stick to commitments from Gabriel Smy

- Radical challenges to management orthodoxy from Lee Bryant

- Meeting such interesting people at the after party

No doubt things will continue to churn and emerge for me as it all settles down, and I'll blog accordingly.

In the meantime, all the videos and slides can be watched here and there are some great graphic summaries here (from Francis Rowland) and here (from Elisabeth Irgens)

There are also longer posts than mine from Charlie Peverett at Neo Be Brave! Lessons from Dare and Banish the January blues – be brave and get talking from Emma Allen.

If you are inspired to go to DareConf in September, early bird with substantial discounts are available until 17th February.

Many thanks to the amazing Jonathan Kahn and Rhiannon Walton who are amazing event organisers - and it's not even their day job. They looked after speakers very well and I got to realise a childhood fantasy of dancing at Sadler's Wells. David Caines drew the pictures.

Who shall we engage, and how intensely?

So you've brainstormed a long (long!) list of all the kinds of people and organisations who have a stake in the policy, project, organisation or issue that you are focusing on. This is what we call stakeholder identification.

What do you do next?

Stakeholder analysis

Now there are lots of ways you can analyse your universe of stakeholders, but my absolute favourite, for its conceptual neatness and the way it lends itself to being done by a group, is the impact / influence matrix.

Notice the subtle but important difference between this matrix, and the one most commonly used by PR and communications specialists, which focuses on whether stakeholders are in favour of - or opposed to - your plans. It would be inappropriate to use this for stakeholder engagement which engages in order to inform decisions, because you will be engaging before you have made up your mind. And if you haven't decided yet, how can stakeholders have decided whether they agree with you?!

Instead, the matrix helps you to see who needs to be engaged most intensely because they can have a big impact on the success or otherwise of the work, or because the work will have a big impact on them. It is 'blind' to whether you think the stakeholders are broadly your mates or the forces of darkness.

Map as a team

Your list is written out on sticky notes - one per note - and the stakeholders have been made as specific as possible: Which team at the local authority? Which residents? Which NGO? Which suppliers in the supply chain?

You have posted up some flip chart paper with the matrix drawn on.

The mapping is ideally done as a team - and that team might even include some stakeholders! During the mapping, everyone needs to be alert to the risk of placing a particular stakeholder in the 'wrong' place, because you don't want to engage with them. It's self-defeating, because sooner or later you will need to engage with the most influential stakeholders whether you want to or not. And sooner is definitely better than later.

You move the notes around until you're all satisfied that you have a good enough map.

Intensity? Transmit, receive, collaborate

When the mapping is complete, then you can discuss the implications: those in the low/low quadrant probably just need to be informed about what's happening (transmit). Those in the diagonal band encompassing both the high / low quadrants need to be asked what they know, what they think and what they feel about how things are now, how they might be in the future and they ways of getting from here to there (receive). NB those in the bottom right corner - highly impacted on but not influential. Vulnerable and powerless. Pay particular attention to their views, make a big effort to hear them, and help them gain in influence if you can.

Those in the 'high/high' corner are the ones you need to work most closely with (collaborate), sharing the job of making sense of how things are now, co-creating options for the future, collaborating to make it happen. Because if they are not on board, you won't be able to design and implement the work.

Prioritise and plan

Now you are in a position to plan your engagement, knowing which stakeholders need mostly to be told, mostly to be listened to or mostly to be collaborated with.

Review and revise

Watch out for people and organisations moving over time. Very often the people in bottom right are the unorganised 'public'. They might be residents or consumers. If they get organised, or their cause is taken up by the media, a celebrity or a campaign group then their influence is likely to increase.

Those in the top left are potentially influential but unlikely to get involved because there's not so much in it for them. Your engagement plan might include helping them to see why their input is useful, and piquing their interest.

So stay alert to changes and alter your engagement plan accordingly.

Reflecting on a change that happened

Here's a nice exercise you can try, to help people base their thinking about organisational change on real evidence. Running workshop sessions on organisational change is a core part of my contribution to the various programmes run by the Cambridge Programme for Sustainability Leadership. This week, a group of people from one multi-national organisation met in Cambridge to further their own learning on sustainability and organisational responses to it. My brief was to introduce them to a little theory on organisational change, and help them apply it to their own situation.

Theory is all very well - I love a good model or framework. But sometimes people struggle to make the links to their experience, or they use descriptive models as if they were instructions.

This exercise gave them time to consider their direct experience of organisational change before the theory was introduced, so that they had rich evidence to draw on when engaging critically with the theory.

Step one - a change that happened

At tables, I asked them to identify a change that has happened in their organisation, of the same scale and significance as they think is needed in relation to sustainable development. All of the tables looked at some variation of the organisation's response to dramatically changing market conditions (engaging with a different customer base, redundancies).

Step Two - four sets of questions

I then asked the groups to discuss how this change really happened (not how the organisation's change policy manual said it should have happened). I offered four sets of questions:

- First inklings e.g. How did you know the change was coming? How did it begin? What happened before that? What happened after that? What changed first?

- People e.g. Who were the main characters who helped the change to happen? Who tried to stop it happening? Who was enthusiastic? Who was cynical? Who was worried?

- Momentum and confirmation e.g. What happened that provided confirmation that this change really is going to happen, that it’s not just talk? How was momentum maintained? What happened to win over the people who were unhappy?

- Completion and continuation e.g. Is the change complete, or are things still changing? How will (did) you know the change is complete?

Step Three - debrief

Discussions at tables went on for about 20 minutes, and then we debriefed in plenary.

I invited people to share surprises. Some of the surprises included the most senior person in the room realising that decisions made in leadership team meetings were seen as significant and directly influenced the way people did things - before the exercise, he had assumed that people didn't take much notice.

I also invited people to identify the things that confirmed that 'they really mean it', which seems to me to be a key tipping point in change for sustainability. Some of the evidence that people used to assess whether 'they really mean it' was interesting: the legal department drafting a new type of standard contract to reflect a new type of customer base; different kinds of people being invited to client engagement events. These 'artifacts' seemed significant and were ways in which the change became formalised and echoed in multiple places.

After the evidence, the theory

When I then introduced Schein's three levels of culture - still one of my favourite bits of organisational theory - the group could really see how this related to change.

Let me know how you get on, if you try this.

The Accompanist

Much food for thought at the joint AMED / IAF Europe 'building bridges' facilitation day last week. I find myself day dreaming and speculating about a particular kind of helping role: the accompanist.

Vicky Cosstick mentioned this in passing, when setting up her session on the glimpses of the future of facilitation. Early in her career, Vicky played this role as part of her training. The role apparently has its origins in spiritual practice, although I'd not come across the term used in this way before.

What does an accompanist do?

The role involves minimal intervention. You attend the work of the group and listen. You write up to a maximum of one page of observations. You pose two or three open questions as part of that. The group can choose to do something with these, or not.

It reminded me of the practice that Edgar Schein describes in Organisational Culture and Leadership, where he too spends much of his time observing.

What a wonderful way to work with a client / self.

What's the minimum we can do, to help?

Facilitation training - can it work one-to-one?

I love to train people in facilitation skills. It's so much fun! People get to try new things in a safe environment, games are played, there's growth and challenge, fabulously supportive atmospheres can build up.

What's the minimum group size for this kind of learning?

How about one?

A group of one

From time to time I'm approached by people who want to improve their facilitation skills, but who don't have a ready-made group of colleagues to train with. I point them towards open courses such as those run by the ICA, and let them know about practice groups like UK Facilitators Practice Group. And sometimes, I work with them one-to-one.

This one-to-one work can also happen because a client doesn't have the budget to bring in facilitator for a particular event, and we agree instead to a semi-coaching approach which provides intensive, just-in-time preparation for them to play the facilitator role. This is most common in the community and voluntary sector.

The approach turns out to be a mix of process consultancy for specific meetings, debriefing recent or significant facilitation experiences, and introducing or exploring tools and techniques.

Preparing to facilitate in a hierarchy

A client had a particular event coming up, where she was going to be facilitating a strategy session for a group of senior people from organisations which formed the membership of her own organisation. She had concerns around authority: would they accept her as their facilitator for this session? She was also keen to understand how to agree realistic aims for the session, and to come up with a good design.

We spent a couple of hours together, talking through the aims of the session and what she would do to prepare for it. We played around with some design ideas. I introduced the facilitator's mandate, and she came up with ways of ensuring she had a clear mandate from the group which she could then use to justify - to them and to herself - taking control of the group's discussions and managing the process. Helped by some coaching around her assumptions about her own authority, she came up with some phrases she was comfortable using if she needed to intervene. We role-played these. She felt more confident about the framework and that the time and energy we'd put into the preparation was useful.

Facilitation skills as a competence for engaging stakeholders

As part of a wider team, I've been working with a UK Government department to help build their internal capacity for engaging stakeholders. As a 'mentor', I worked with policy teams to help them plan their engagement and for one team, this included helping a team member get better at meeting design and facilitation. He already had a good understanding of the variety of processes which could be used and a strong intuitive grasp of facilitation. We agreed to build this further through a (very short) apprenticeship approach. We worked together to refine the aims for a series of workshops. I facilitated the first and he supported me. We debriefed afterwards: what had gone well, what had gone less well, and in particular what had he or I done before and during the workshop and what was the impact. He facilitated the next workshop, with me in the support role. Again we debriefed. We sat down to plan the next workshop, and I provided a handout on carousel, which seemed like an appropriate technique. I observed the next two workshops, and again we debriefed.

Instead of a training course

I worked with a client who wanted to develop his facilitation skills and was keen to work with me specifically, rather than an unknown and more generic open course provider. I already knew his context and he knew I'd have a good appreciation of some of his specific challenges: being in the small secretariat of what is essentially an industry leadership group which is trying to lead a sustainability agenda in their sector. His job is to catalyse and challenge, as well as to be responsive to members. So when he is planning and facilitating meetings, he will sometimes be in facilitator mode and sometimes he will need to be advocating a particular point of view.

Ideally, I'd have wanted to observe him in action in order to identify priorities and be able to tailor the learning aims. But the budget didn't allow for this.

We came up with a solution which was based on a series of four two-hour sessions, where I would be partly training (i.e. adding in new 'content' about facilitation and helping him to understand it) and partly coaching (i.e. helping him uncover his limiting assumptions and committing to do things differently). The sessions were timed to be either a bit before or a bit after meetings which he saw as significant facilitation challenges, so that we could tailor the learning to preparing for or debriefing them. The four face-to-face sessions would be supplemented by handouts chosen from things I'd already produced, and by recommended reading. We agreed to review each session briefly at the end, for the immediate learning and feedback to me, and partly to model active reflection and to get him into the habit of doing this for his own facilitation work.

In our initial pre-contract meeting, we agreed some specific learning objectives and the practicalities (where, when). Before each session, we had email exchanges confirming what he wanted to focus on. This meant I could prepare handouts and other resources to bring with me.

And this plan is pretty much what we ended up doing.

He turned out to be very well suited to this way of learning. He was a disciplined reflective practitioner, making notes about what he'd learnt from his experiences and bringing these to sessions. He was thoughtful in deciding what he wanted to focus on which enabled me to prepare appropriately. For example, in our final session he wanted to look at his overall learning and to identify the learning edges that he would continue to work on after our training ended. We did two very different things in that session: he drew a timeline of his journey so far, identifying significant things which have shaped the facilitator he is now. And we used the IAF's Foundational Facilitator Competencies to identify his current strengths and learning needs.

Can it work?

Yes, it's possible to train someone in facilitation skills one-to-one. This approach absolutely relies on them have opportunities to try things out, and is very appropriate when someone will be facilitating anyway - trained or not. The benefits are finely tailored support which can include advice as well as training, coaching instead of 'talk and chalk', and debriefing 'real' facilitation instead of 'practice' session.

There are downsides, of course. You don't get the big benefit which can come from in-house training, where a cohort of people can support each other in the new way of doing things and continue to reflect together on how it's going. And you don't get the benefit of feedback from multiple perspectives and seeing a diverse way of doing things, which you get in group training.

But if this group approach isn't an option, and the client is going to be facilitating anyway, then I think it is an excellent approach to learning.

Position, Interest, Need - uncovering latent consensus using PIN

Sometimes our work involves facilitating conversations among people who know that they disagree with each other. They may be professional campaigners, politicians or lobbyists. They may be householders or developers. They may be in the room because a sudden row has blown up triggered by news of a forthcoming decision about funding, planning permission or a change in the law.

Whatever has led to it, the people I'm thinking of have already established a 'position' about the topic, and assume that their job in the meeting is to advocate and defend that position.

Defending a position

Defending a position leads to people asserting certainty about causes, consequences and facts, often more certainty than is justified by the current state of knowledge and analysis. It encourages people to dispute the facts put forward by others, and to question their motives. People defending a position often build such an edifice of certainty around themselves that it is very hard for them to move away from their initial position, even if they want to.

The things said about those who don't agree with the position can be damaging to working relationships and lead to a decrease in trust, making subsequent conversations harder.

Win/win or win/lose?

Positional conversations assume a win/lose paradigm. But what if it were possible to find a win/win? You can only discover the potential for a win/win if you move beneath the positions and discover the interests and needs. (I could tell you about boogli fruit, but I'd have to kill you.) What has led people to develop their positions? What interests are served by those positions? What are the needs which are met through those interests?

Below the inversion

I was first introduced to this concept by Pippa Hyam and Andrew Acland in their training for Environmental Resolve, an initiative to find consensus to thorny situations run under the umbrella of The Environment Council. Up until that point, I don't think I'd really understood the difference between a really great compromise, and a true win-win. It was a fairly life-changing experience.

Using questions to walk down the mountain

How do you help people move away from positions and towards their interests and needs?

One approach is to help people avoid getting positional, at least too early on in the conversation. This may be hard to avoid: positions may already have been taken. But it you aren't in that situation yet, the facilitator can help the group enormously by holding them in the uncertainty and exploration phase: the not-knowing. Invite people to tell their stories and share their perspectives about the problem, issue or desired future in an open way. If options have been generated, get people to explore their pros and cons without asking them to express a preference.

If positions have already been expressed, then the facilitator's greatest asset is their ability to ask straight questions and then listen in a genuine spirit of curiosity. Using questions like "what would that give you?" or asking a participant to "tell us more about why that's something you'd like to see" invites people to say more about the things that underlie their positions.

Listening really well, reflecting back on what's been said to check understanding and show that the person has been heard, and asking further questions which clarify or invite expansion - these interpersonal skills are invaluable.

What's up for grabs?

Spurred on by discussions over at the Involve blog, I want to share a really useful framework for those of you who are thinking about engaging stakeholders or (sections of) the public while you decide what to do about something. At the start, discussions within the organisation which is asking for input need to establish clarity about what's alread fixed, what's completely open and what there are some preferences about but where there is room for change.

Pie Chart: Lindsey Colbourne

Not negotiable - At the start of your engagement process it is likely that what's decided (and thus not negotiable) may be at the level of overall objectives, and timescales. For example, a Government department may have a policy objective and a legal deadline to meet. A local council may know that it wants to revamp a local park, and have a potential funding source whose criteria it needs to meet.

Negotiable - You may have some existing preferences, ideas or initiatives which have been piloted and could be rolled out. There may be some technical information which will inform the decision or be used to assess options. There may be criteria which you are bound to, or want to use, but haven't yet applied to the options.

Open - There will be aspects of the decision which you have no preference about and where the decisions can in effect (even if not in law or within your organisation's own rules) be delegated to others.

Remember that you will also have decided-negotiable-open aspects to your engagement process - the people you talk to, the points at which you engage them, the methods and channels which are used.

The conversation you have internally with your team about what goes in each slice of the pie can often be dramatically useful: flushing out assumptions which have hitherto been hidden, and exposing disagreements within the team in the safety of your planning conversations rather than in the less forgiving gaze of stakeholders.

The pie slices shift over time

At the start of the process, it's likely that the 'decided' slice is slimmer than the other two. As the process unfolds, things usually shift from 'open' to 'negotiable' and from 'negotiable' to 'decided'. Principles and assessment criteria get agreed. Ways of working are negotiated. Working groups or consultation processes are established. Exploratory conversations crystalise into options which get fleshed out and then assessed. Some options get discarded and others emerge as front-runners.

Sometimes, things can move in the other direction: when opposition is so strong that you have to think again, or when new information emerges which shows that ways forward which had seemed marginal are now much more likely to work. In extreme circumstances, this may lead to the initiative being abandoned altogether. The debacle over England's publicly-owned forests is an example of this.

Tell people what's 'up for grabs'

There's no point asking people what you should do about something if you have already made up your mind.

By all means ask for feedback which will help you communicate your decisions more clearly. Understanding people's concerns and aspirations means you can address them directly in your explanations about why you have made a particular decision and how to expect to implement and review it.

Do people the simple courtesy of letting them know which aspects of situation you are most keen to get their feedback and ideas about - which information will most helpful in informing the decision, the dilemmas you'd like to think through with them, the innovative ideas you'd like to test out.

That way, everyone's time is spent where it can make the most difference.

Simples.

Thanks to...

Acknowledgements to Lindsey Colbourne and others at the late lamented Sustainable Development Commission, InterAct Networks, Sciencewise-ERC and the Environment Agency who have been developing and working with this framework over the last few years.