Holding out for a hero

We’re in a hole and we’re not making headway on the huge challenges that face us as a species and as a society. Our so-called leaders shy away from action which isn’t incremental and easy. We’re caught in a web of interlocking dependencies shoring up the status quo. And meanwhile environmental limits are being breached every way we turn. Why doesn’t somebody DO SOMETHING?

But hang on, what if we are the people we’ve been waiting for?

We, too, can be tempered radicals, positive deviants or social intrapreneurs – different labels for essentially the same ambiguous role: change makers on the inside of our organisation or community, wherever this may be.

This antidote to ‘great man’ leadership is explored in two books: The Positive Deviant (Parkin) helps you prepare and plan, Leadership for Sustainability (Marshall et al) is an edited collection of tales from fellow travellers, shared with a degree of honesty and openness which is unexpected outside the safety of a coaching conversation.

Who will show leadership?

Both books rightly assert that leadership can come from anywhere. The leader may be the boss, but leadership is something any of us can practice. And that’s lucky, because we need whole systems to change, not just individual organisations. And systems don’t have a boss. Leadership is necessarily distributed throughout the system, even if some people have more power than others.

Parkin’s positive deviant is someone who does the right thing

“despite being surrounded by the wrong institutions, the wrong processes and stubbornly uncooperative people”.

They work to change the rules of the game. Rather than waiting for stepping stones to appear they chuck in rocks, building a path for others as they go.

Effective leadership comes from surprising places within hierarchical structures, and can arise in situations where there isn’t any formal organisation at all. This makes the positive deviant quite close to the tempered radical, yet Meyerson's work is a surprising omission from Parkin's index and bibliography.

Marshall et al see leadership

“as much [in] the vigilante consumer demanding to know where products have come from as [in] the chief executive promoting environmentally aware corporate practices.”

So none of us is off the hook.

What kind of leaders do we need?

If we are all in a position to show leadership, which qualities do we need to hone, to help us be really good at it?

Parkin is clear that we need to be ethical and effective.

Ethical

As Cooper points out in one of the chapters of Leadership for Sustainability, the scale of the transformation implied by how bad things are now means that doing things right is not enough: we need to do the right things.

It is not enough to show leadership merely in the service of your own organisation or community. With sustainability leadership the canvas is all humanity and the whole planet (All Life On Earth including Us, as Parkin puts it). Regular readers of this blog, and participants on the Post-graduate Certificate in Sustainable Business will know that this is one of the distinctions I make between 'any old organisational change' and 'organisational change for sustainable development'. See the slide 22 in the slide show here for more on this and other tensions for sustainability change makers.

To do this, the Positive Deviant has a ‘good enough’ understanding of a range of core sustainability information and concepts, and Parkin summarises a familiar set of priority subjects. Less familiar are the snippets of sustainability literacy from classical antiquity which liven things up a bit: Cleopatra’s use of orange peel as a contraceptive and Plato’s observations of local climatic changes caused by overenthusiastic logging.

If you already know this big picture sustainability stuff, you may feel you can safely skip Parkin’s first, third and fourth section. Not so fast. I read these on the day DCLG published its risible presumption in favour of sustainable development. DCLG’s failure to mention environmental limits and the equating of sustainable development with sustainable building is a caution: perhaps people who might be expected to have a good understanding of sustainability should read this section, whether they think they need it or not!

Effective

We need to understand the kinds of problems we’re facing. Parkin offers use Grint’s useful sense-making triad to understand different kinds of problems which need different approaches:

- tame (familiar, solvable, limited uncertainty),

- wicked (more intractable, complex, lots of uncertainty, no clear solutions without downsides) and

- critical (emergency, urgent, very large) problems.

The problems of unsustainability are very largely wicked (e.g. breaking environmental limits), and some are critical (e.g. extreme weather events).

Complex, uncertain and intractable situations require experimentation and agility, according to Marshall et al. Parkin echoes this:

“By definition, we’ve not done sustainable development before ... so we are all learning as we go.”

Marshall et al go further:

“we doubt if change for sustainability can often be brought about by directed, intentional action, deliberately followed through.”

Superficial change may result, but not systemic transformation. So leadership demands that we embrace uncertainty and release control. This is pretty much what I'm trying to articulate here, so you'd expect me to agree. I do.

Parkin is dismissive of understandings of leadership in the context of chaos or distributed systems. She may be right that it is a perverse choice to lead in this way if you are within an organisation which functions well in a predictable external context. But as we have seen, leadership is most urgently required in situations which are much less simple than this, where there isn’t an obvious person with a mandate to be 'the leader'. Dispersed leadership is a more accurate description of reality and a more practical theory in these situations. There are some well-thought of organisational consultants and theorists worth reading on this. For example Chris Rodgers and Richard Seel have both influenced my thinking. AMED's Organisations&People journal regularly carries great articles if you want to explore this side of things.

From the installation of secret water-saving hippos in Cabinet Office (Goulden in Leadership for Sustainability) to John Bird setting up the Big Issue or Wangari Maathai founding of the "deliciously subversive" Green Belt Movement (some of Parkin’s choices as Positive Deviant role models), the reader can’t help but be personally challenged: how do I compare, in my leadership? Am I ethical? Am I effective?

How will we get them?

How can we make ourselves more effective as leaders, where-ever we find ourselves? How can we help others to show leadership?

These questions bring us to the educational and personal development aspect of these books.

Education and training

Leadership for Sustainability is a collection of personal stories gleaned from people who have been through the MSc in Responsibility and Business Practice at the University of Bath’s School of Management (succeeded by Ashridge Business School’s MSc in Sustainability and Responsibility and the MA in Leadership for Sustainability at Lancaster University School of Management). Parkin designed Forum for the Future’s Masters in Leadership for Sustainable Development. So you can expect that both books have something to say about how we educate our future leaders.

Parkin dissects the ways business schools have betrayed their students and the organisations they go on to lead. Unquestioningly sticking to a narrow focus of value, not understanding the finite nature of the world we live in, and avoiding a critique of the purpose of business and economy, by and large they continue to produce future leaders with little or no appreciation of the crash they are contributing to.

Marshall and her colleagues have shown leadership in this field, using a Trojan horse approach by setting up their MSc in the heart of a traditional business school, and seeding other courses. Positive deviance in practice!

Personal development

Formal training aside, we can all improve our sustainability leadership skills.

Parkin argues that as well as having a ‘good enough’ level of sustainability literacy, Positive Deviants need to practice four habits of thought. These are:

- Resilience – an understanding of ecosystems, environmental limits and their resilience, rather than the personal robustness of the change maker.

- Relationships – understanding and strengthening the relationships between people, and between us and the ecosystems which support us.

- Reflection – noticing the impact of our actions and changing what we do to be more effective, as a reflective practitioner.

- Reverence – an awe for the universe of which we are a part

Action research

Of those four habits of thought, reflection is the one closest to the heart of Marshall’s Leadership for Sustainability approach.

Marshall, Coleman and Reason are committed to an action research approach, seeing it as

“an orientation towards research and practice in which engagement, curiosity and questioning are brought to bear on significant issues in the service of a better world.”

In her chapter, Downey reminds us of the ‘simple instruction at the heart’ of action research

“take action about something you care about, and learn from it.”

Marshall et al tell us that action research was central to the structure and tutoring on their MSc. I have to confess to being unclear about the distinctions between action inquiry, action research and action learning. Answers in the comments section, please!

Marshall et al’s action learning chapters are useful to anyone involved in helping develop others as managers, coaches, consultants, teachers, trainers and so on – required reading, in fact, for those wrong-headed business schools which Parkin criticises so vehemently.

The power of the action research approach shines through in the collection of twenty-nine stories, which made this book – despite the somewhat heavy going of the theoretical chapters – the most compelling sustainability book I’ve read in a long time. People have taken action about things they care about, and they have learnt from it.

Their stories demonstrate that we encourage people to show leadership in part by allowing them to be humble and to experiment, not by pretending that only the perfect can show leadership. The stories do not trumpet an approach or sell us a technique. They are travellers’ tales for people who’ll see themselves in the narrative, and be inspired and comforted by it.

What does it feel like, to be this kind of leader?

Does this kind of leader sound like you yet? It could be – anyone can show leadership. But perhaps you’re sceptical or looking for a reason why it can’t be you? It sounds like a lot of hard work and there’s no guarantee of success.

Marshall and her colleagues on the MSc course have evidently created a safe space for people to reflect about their doubts and uncertainties as well as their hopes and insights. Chapters including this kind of personal testimony from people like Gater, Bent and Karp are intriguing, dramatic and engaging.

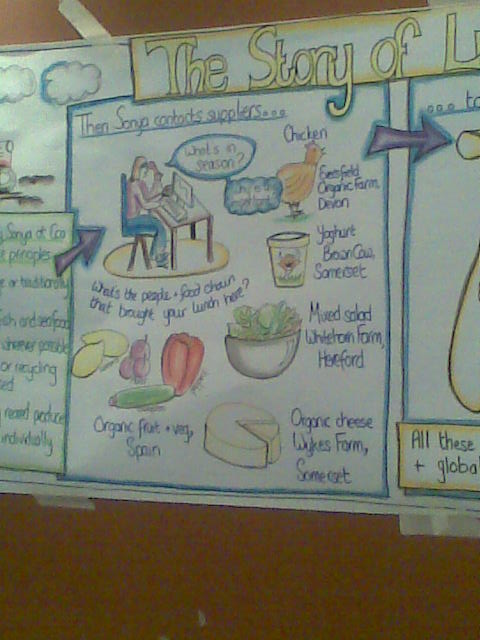

Karp’s story about food procurement shows difference between action learning approach and leader as hero – she’s as open about the set-backs as the successes.

I instantly recognised Bent’s description of holding professional optimism with personal pessimism, and many people I know have had that same conversation: wondering where their bolt-hole will be, to escape the impacts of runaway climate change.

Gater’s story in a brilliantly honest account of his work within a mainstream financial institution, moving a certain distance and then coming up against a seemingly insurmountable systemic challenge. In a model of authentic story-telling, he describes tensions I have heard so many organisational change agents express. He talks about visiting his colleagues ‘in their world’ and inviting them to visit him in his. At the end of his story, the two worlds remain unreconciled,

“but it was okay – I had done what I could do as well as I believe I could have done it, and that had to be enough.”

Concluding

Both books start from the premise that we can’t wait for others to show leadership – we need to show leadership from where we are.

But we know that’s hard: Downey reminds us that

“…those who protect the status quo get rewarded for the inaction that slows down change, while disturbers-of-the-peace who send warning signals are disparaged, demoted or dismissed.”

But for her that’s not an excuse to hang back:

“we are not too small, and there is no small act. Either way we shape what happens.”

Transparency alert: Penny Walker is an Associate of Forum for Future, of which Sara Parkin is a Founder Director. Penny has also been a visiting speaker on the MSc in Responsibility and Business Practice run by Judi Marshall, Gill Coleman and Peter Reason, as well as being a tutor on what might be seen as a competitor course, the Postgraduate Certificate in Sustainable Business run by the Cambridge Programme for Sustainability Leadership in conjunction with Forum for the Future.

A shorter version of this review was first published in Defra's SDScene, here.