Photo: Robert Tadlock, flickr

In the last couple of months I have taken up climbing again, after a break of about ten years.

It’s exciting.

The atmosphere at the indoor climbing centre I go to is upbeat, dynamic, friendly.

When you hire out a carabiner and belay device - the small, beautifully engineered bits of metal which could save your life - the heavily pierced man in the hire shop will accept an RSPB membership card instead of a credit card as a deposit. It’s that kind of place.

The background music is familiar and chosen to make you smile: ABBA, early 80s pop, 70s funk.

There are cheerfully written signs dotted around to point you to the café, yoga room and organic garden as well as to the more challenging ‘Stack’ and ‘Catacombs’ – fancifully named climbing walls. Notices tell you that dogs are welcome, outside of peak times, but must not be tied to the safety equipment.

There are people whose job it is to set routes that you climb on the walls. They bolt on the brightly coloured artificial ‘holds’ in carefully planned patterns that allow for all levels: starting at an easy peasy grade 3 and carrying on right up to a surely impossible 8a. They include tricky little challenges that you have to puzzle out and then implement – can I really get my foot that high and then push down on my hand to shift my weight on it?

Sometimes!

But don’t be fooled by the jollity and bright colours. 12 metres up is still 12 metres up, even if the holds you are balanced on look like spotted turtles or alien jellies.

I climb tied to a rope which runs from my harness through a metal chain fixed at the top of the wall, then drops back down to the bits of metal secured via another harness to my climbing partner. This is known as “top roping” and the act of holding and carefully taking in the rope - which the non-climber does - is called ‘belaying’. Your belay is the person in charge of making sure the rope will save you.

Don’t worry, there is more to this post than a lesson in climbing terminology!

If you climb this way, with a partner who is your belay, there’s something a bit funny – in fact, a bit alarming - that I’ve been taught to do at the beginning of a session.

When you have climbed up high enough that your feet are above your belay’s head – around two metres - you are supposed to fling yourself from the wall, without warning the belay.

Why would you do that?

You fling yourself from the wall to prove to you both, the climber and their partner, that they will hold you.

And the beautiful symmetry of the partnership means that as soon as you are back on solid ground and have wiped the sweat off your hands onto your trousers, you swap over and belay your partner as they make their way up the route they have chosen.

You can also climb without a partner.

It’s not just humans who might stop the rope slithering through, halting your rapid descent and leaving you swinging gently instead of writhing in agony on the floor.

Where I climb, there are also automatic belay devices – simple mechanisms which take up the slack rope for you and, like a car safety belt, stop you if you fall.

So the thing keeping you safe when you climb – actually, keeping you safe when you fall - might be a person or it might be something else. You test it just the same. You fling yourself off the wall from a relatively safe position.

I am afraid of heights and I am especially afraid of falling. Both those fears magnify a third fear – I am afraid of not being in control.

Even a couple of metres off the ground, I really don’t want to fling myself from the wall. My palms sweat. My feet - already in a gripping shape due to the tight, tight climbing shoes - curl further inwards in a reflex reaction to the very thought of falling. They are trying to grasp the footholds. I psych myself up and chicken out.

We fling ourselves from the wall at a safe height, so that we can be sure of being safe when we need to make a truly risky move twelve metres up.

Why we fling ourselves off the wall

In my life, I have put off doing some things that I really want to do, for fear of how bad it will feel if I fail. I am afraid of the shame, the crushing of my self-confidence, the public humiliation.

Your fears may be different. These are mine and I suppose they must be very precious to me because I still cling on to them after all this time.

What’s enabled me to go ahead and do the exciting things anyway – including just in this last year - is my previous experience of coming back from failure and from the excruciating shame I feel when I think I have failed.

This fear of failing is strong stuff.

Even the anticipation of that shame is really powerful too. I don’t have to actually fail, to feel the shame. I just have to imagine it happening.

In fact my palms are sweating now!

I have lately come to accept that I will feel bad while I contemplate and plan my daring actions. I will fall off the wall. I still feel bad – I haven’t learnt to avoid the fear, and I’m not sure I ever will. It’s more that I now see it as the price I pay for doing something really cool.

I know that feeling bad is temporary. I have strategies for feeling better again. I have a coach, a 'thinking partner', supportive groups, yoga. When I fall, and I do, I am caught.

Taking a test fall

I’m on the climbing wall. My belay partner is relaxed and ready. They have done this before, they trust the ironmongery and the rope. They trust me. They want me to experience the exhilaration and triumph of beating the challenge from the fiendish route-setter, of getting to the top.

And yet, and yet….

OK, this is it. If I wait any longer, my pretend fall won’t be enough of a surprise to test the team.

I reach for a hold with my arm, pushing away from the wall with my legs at the same time. I’m airborne and falling for a split second, before the rope goes taut and I’m jerked to a stop.

And breathe.

A few minutes later, I’m 12 metres up, stretching for a hold I can’t quite reach, but launching towards it anyway because - what’s the worst that could happen?

I’m no gecko, but knowing I’m roped up to someone, or something, that will catch me means I’ve definitely left the grade 3 routes behind.

In fact, if I’d never fallen and been caught, I never would have made it beyond beginner graded climbs.

In our lives, we can all be climbers. We can all take practice falls. We can all belay for someone else.

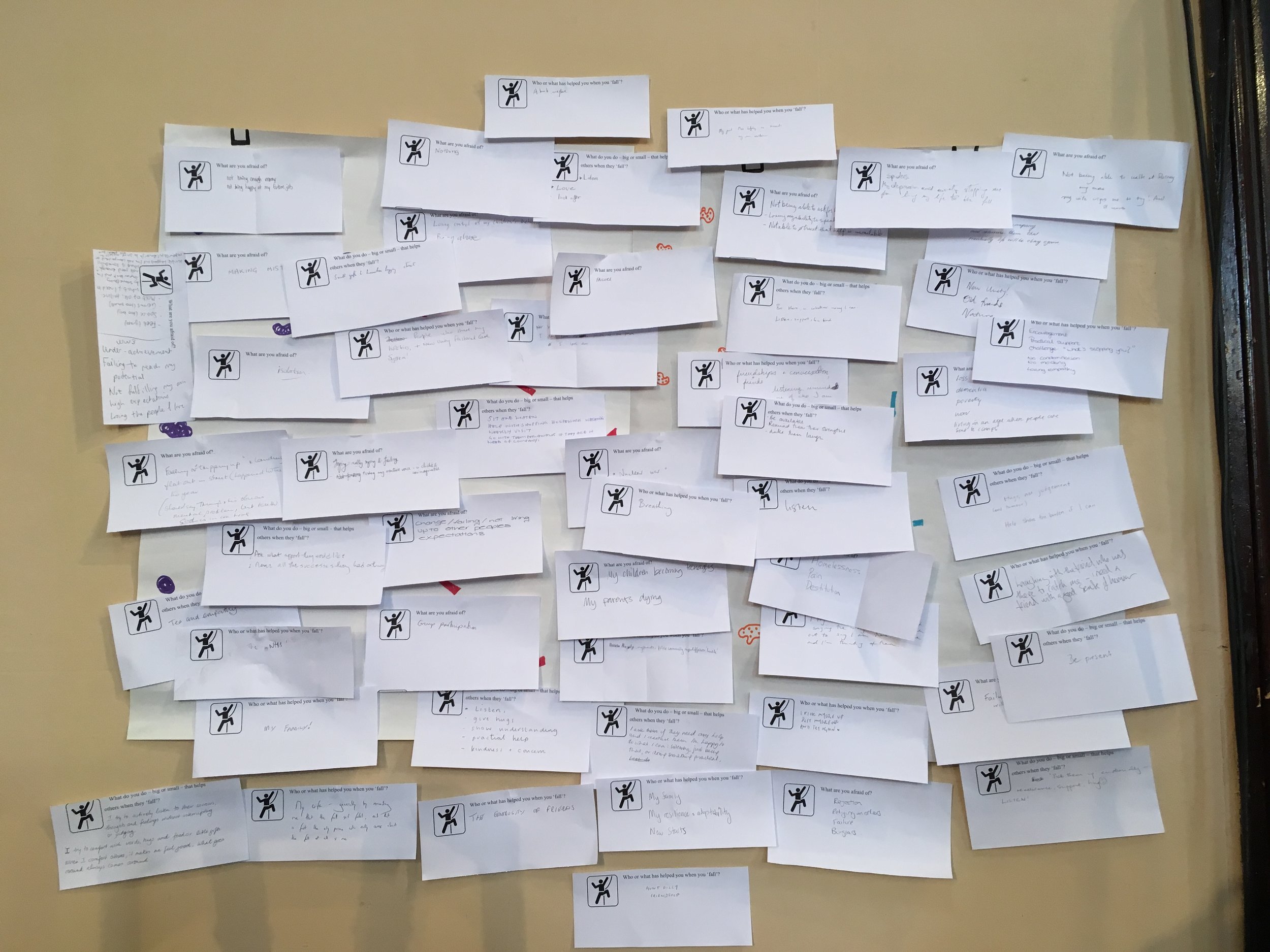

Over to you

· What are you afraid of, that holds you back from doing the cool stuff?

· Who or what catches you when you fall?

· Who do you catch, when they fall?

Knowing that we will be caught when we fall – by a person or by something else - enables us to do greater things.

Let us climb, fall, be caught. Let us catch others.

First outing...

This blog post is based on a presentation I made at this weekly gathering of like-minded fellow-travellers. There's a periscope recording here.